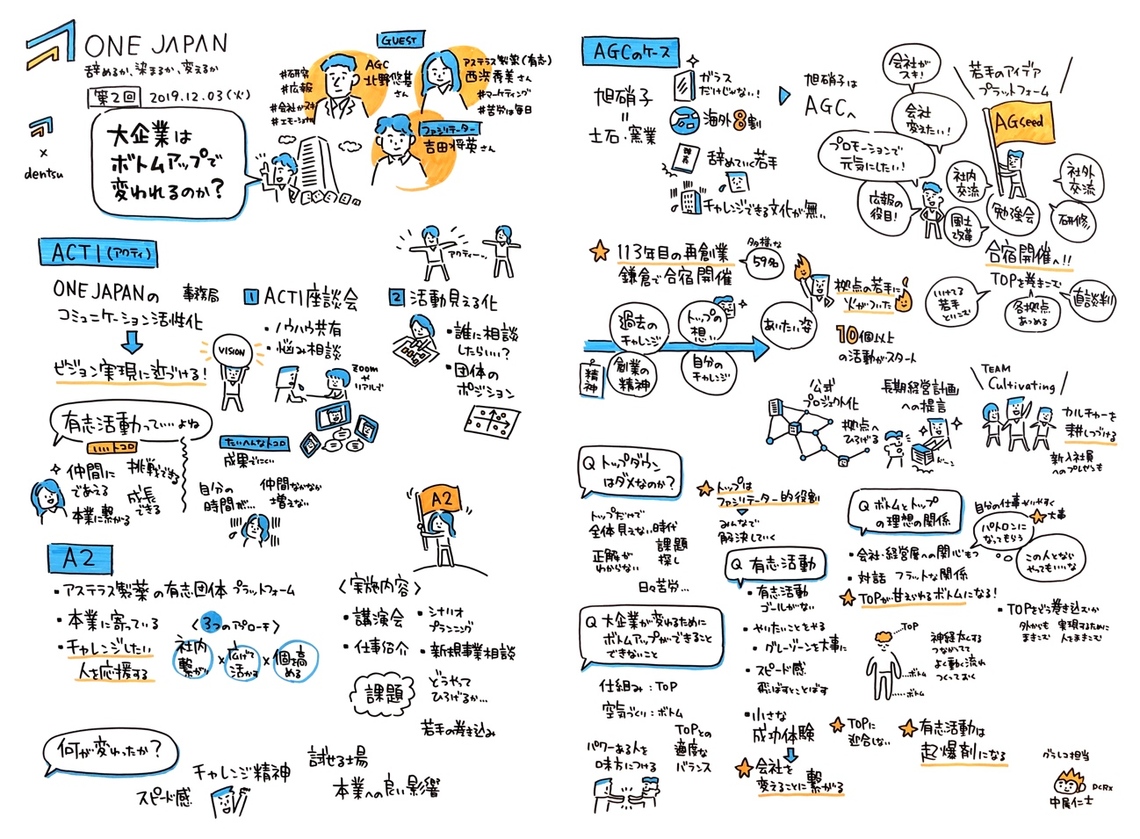

Titled "Quit, Conform, or Change," this series has thus far explored new "possibilities for large corporations" through event reports based on several themes surrounding corporate transformation. Starting with the third installment, we will examine these possibilities by interviewing individuals directly involved in transformation efforts at companies belonging to ONE JAPAN member organizations.

What is needed for young employees to drive transformation within large corporations that have established solid business models and traditions?

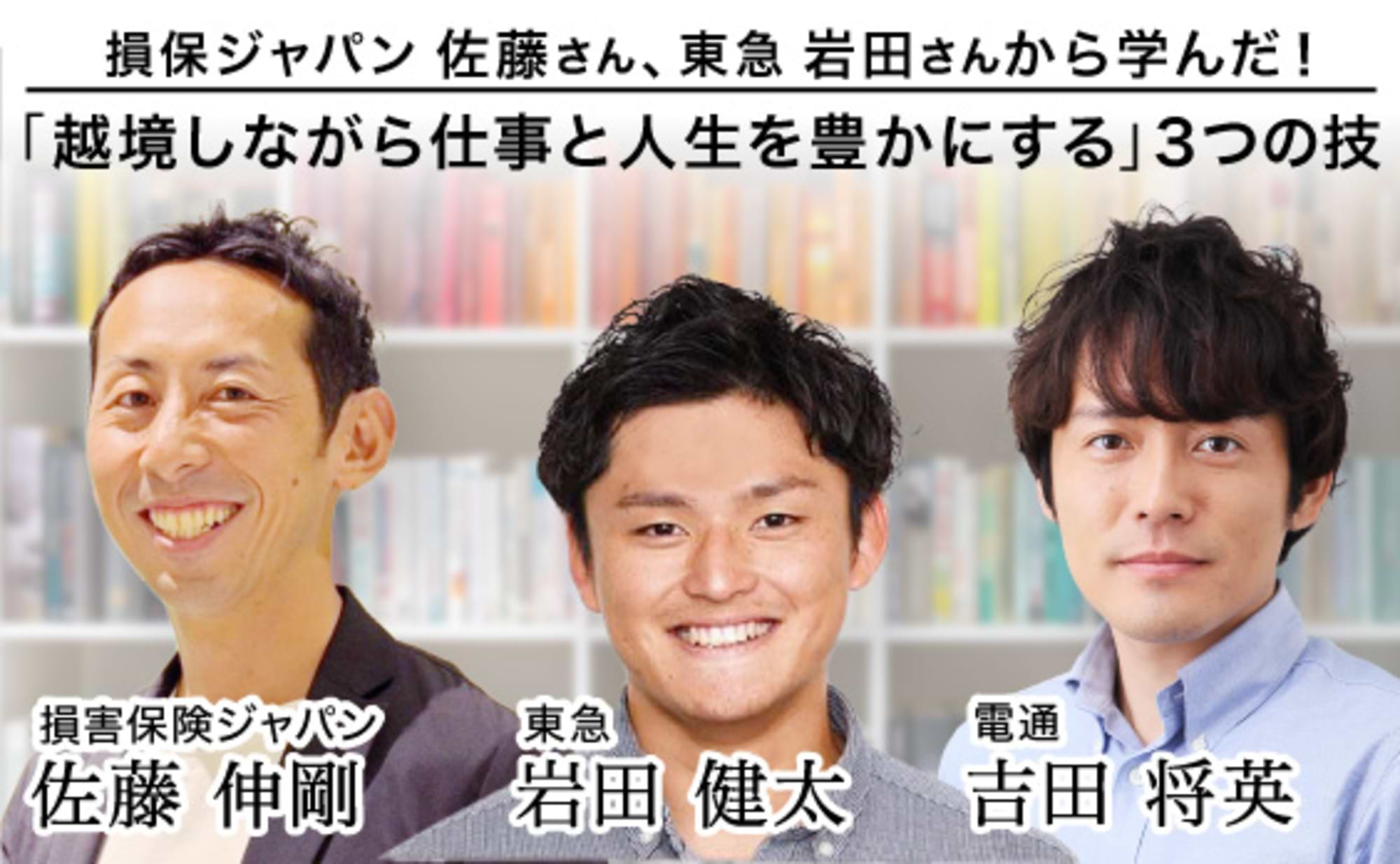

Yoshida: Mr. Fukui, you currently manage the Tokyu Accelerate Program at Tokyu Corporation, and you also launched an accelerator program at your previous employer, Japan Post. What prompted you to embark on this path as an accelerator?

Fukui: I've been affiliated with three companies so far, including my secondment assignments. I joined Japan Post right after graduation, and in my fourth year, I requested a secondment to Lawson. My third company is Tokyu, where I am now. The catalyst was my two-year experience at Lawson.

At Lawson, I witnessed firsthand how the leadership team—including former presidents Takeshi Shinano and Motoichi Tamatsuka, and current president Sadanobu Takemasu—demonstrated strong leadership, uniting employees toward a common goal. While large corporations often become siloed organizations, Lawson transcended that with a sense of co-creation and speed. In my words, it was a company with a "challenger spirit" to work for.

Returning to Japan Post, I was fired up, thinking, "I'll change this company too, taking on challenges that transcend organizational barriers," just like the professional managers and employees I'd seen at Lawson. However, different organizations naturally require different approaches, and I struggled. Around that time, there was an open call for members to participate in an event called "Machiten," focused on regional revitalization and open innovation. I joined that team, and it became my gateway into business creation. However, since the team was primarily young members juggling their regular duties alongside this project, it took a significant amount of time to shape new collaborative initiatives.

Based on these experiences, I realized that to truly change a company, you need to create a program that involves the decision-makers from the outset. That's why I launched the open innovation program.

Yoshida: When people want to change the status quo, some, like Mr. Fukui, try to change it themselves, while others seek to change their environment by moving to a different company. After returning from your assignment, you mentioned two setbacks. What led you to overcome them and develop the mindset of "involving the entire company's decision-makers"?

Fukui: Since joining the company, three events shaped my conviction to improve and transform it. The first was the Great East Japan Earthquake. Shortly after the disaster, I was dispatched to post offices and evacuation centers in the affected areas. There, I witnessed a postal delivery worker. He had apparently been diligently making deliveries without complaint since right after the quake. The stationmaster I was with told me, "His wife and child were swept away by the tsunami and are still missing." Learning this made me deeply contemplate the social mission and very reason for Japan Post's existence.

The second was gaining an objective perspective on Japan Post while seconded to Lawson. At the time, I proposed a joint project between the two companies, and during my Lawson assignment, I worked alongside Japan Post colleagues. It involved a pilot project engaging several post offices, which wasn't part of the staff's core duties. Yet, everyone cooperated tremendously with the initiative. Witnessing this, I realized there were far more people than I imagined who genuinely wanted to improve the company. I felt that with these people, we could change the company – we had to.

The third moment was when I asked an external partner to collaborate on realizing a business plan I'd developed for Machiten. Their response was, "What can a bunch of young guys from a big corporation, weighed down by its operations, really accomplish?" Looking back, that criticism was valid. Projects involving only staff-level personnel can't drive change. But at the time, it sparked a rebellious spirit in me (laughs).

So I seriously considered how to move the company. I concluded that getting agreement from all relevant management—not just the president or some executives—was essential. I secured not only the president at the time, but also all executives and department heads from the postal/logistics and business development divisions as project mentors. I created a situation where everyone—from the management team, to middle management, to the operational staff—would cooperate and work together.

Yoshida: Looking at large corporations, I often sense many people suffering from a defeatist attitude, thinking "our company is just..." It's not quite "a scar becomes a dimple" (meaning that if you like someone, even a scar looks like a dimple), but the same facts can be perceived differently by each employee, right? I think Mr. Fukui had the ability to view the company's current state positively, and that attitude spread to those around him.

Fukui: To use that metaphor, when I feel frustrated and want to change things, I see the current state as a scar. When I feel like giving up, I see it as a dimple. Another crucial point is that people with a negative mindset shouldn't be involved in projects in the first place. In companies with thousands or tens of thousands of employees, there will inevitably be people who mock employees with a mindset like mine as "overly ambitious."

From the perspective of a single company unit, having people with both mindsets is meaningful for survival. However, when attempting something new, I believe an environment free of negative energy is preferable.

"Star-Making for All" to Engage Everyone

Yoshida: The strategy you adopted at Japan Post, Mr. Fukui, wasn't a "single-pronged approach" where you only aligned with management who shared your views, nor was it tied to typical internal factions—it seemed to transcend them. How did you arrive at that mindset?

Fukui: The trigger was witnessing corporate politics firsthand. This might be a common occurrence in large corporations, but regardless of the depth of the divide, differences in policy and perspective are unavoidable within any organization. However, I felt uneasy about my career being swayed by such factors and saw it as a risk. To overcome this and continue pursuing what I believed was necessary to change the company, I concluded that instead of aligning with factions or specific individuals, I had to persuade every relevant executive and middle manager. This conviction hasn't changed since I joined Tokyu.

Yoshida: Human relationship dynamics are incredibly complex. Some people even dislike someone precisely because they're well-liked by everyone else...

Fukui: Leadership is often categorized into two types: transformational leadership, which inspires people by presenting a vision and gaining their empathy, and transactional leadership, which motivates people by showing them the benefits. I considered which type of conversation would be most effective with each executive based on the situation at hand, and adjusted my explanations accordingly.

For example, with transactional leaders, I focused on making them see the benefits of cooperating with the initiative. Even in Japan Post's Accelerate Program, some executives were initially reluctant to cooperate. So, when explaining a project that required their support, I deliberately slipped a draft press release bearing the president's name as the chair of the judging panel into the materials, making sure it stood out (laughs).

Yoshida: It takes courage to oppose a press release bearing the president's name.

Fukui: But if you only use transactional communication to get people on board, they might flip-flop at the slightest change in circumstances. We focused primarily on transformational communication. To get them to say, "I'm cooperating to support Fukui," we deliberately avoided mentioning the press release during meetings. Instead, we persistently explained the significance of the initiative beyond that executive's immediate purview.

Yoshida: So you prepared a compelling justification individually tailored to each executive's needs.

Fukui: Given how far I went, the crucial part was "ensuring everyone involved came out ahead." I not only prioritized each person's sense of satisfaction but also poured my full effort into the project so they could feel their decision was the right one.

Yoshida: I see this role of involving others, or acting as a coordinator, as distinct from your role as the project planner. You seem quite adept at switching between them. What's your secret to maintaining that balance?

Fukui: I believe that "the substance of the plan is crucial for engaging others," and "engaging others is crucial for making the plan happen." Compared to before, there's now a wealth of know-how available on corporate innovation, including open innovation and accelerator programs. There should be plenty of references on what kind of plan to create to engage key people. If you thoroughly refine your company's own "WHY," the plan itself will be polished, and then you can focus on engaging others.

Yoshida: That said, there are still people who are hard to convince, right?

Fukui: The key point is that a head-on approach isn't the only option. When I needed to persuade someone, I actually enlisted the help of someone they trusted.

Media exposure also helped with persuasion. A manager who saw my interview article told me, "Fukui-san, you're impressive. I want to support you." When appearing in external media, I consulted with the PR department beforehand about the wording in the article. It's an activity that simultaneously shows "I'm doing this while properly considering the company" and increases the number of stakeholders.

During interviews, I also made sure members involved in the project, including executives and middle managers, were featured as much as possible. Especially early on, I intentionally had middle managers known as the president's confidants participate in media interviews. Internally, this created the impression that "a project involving those people must be solid," which helped increase support.

Yoshida: In large corporations, internal interests are complexly intertwined, so securing influential allies early on might be a golden rule. On the other hand, some people are bad at office politics, while others prioritize reading the room above all else. Mr. Fukui, you seem to understand the balance between the "ground game" you just described and direct confrontation.

( Continued in Part 2 )