For projects focused on "0→1" (creating something from nothing), it's about how well you lay the groundwork for organization and commercialization. Once that foundation is in place, it's the "1→10" stage—how well you can complete the organization or business. Even though we call them accelerators, their role varies by company, so the definition of success changes too.

Furthermore, the qualities required of leaders and members change depending on the nature of the project. For a company that has achieved "0→1," it's crucial to evolve into a structure capable of "1→10." For example, if the person leading that project is suited for "0→1," having them continue to handle "1→10" in the next phase might not work.

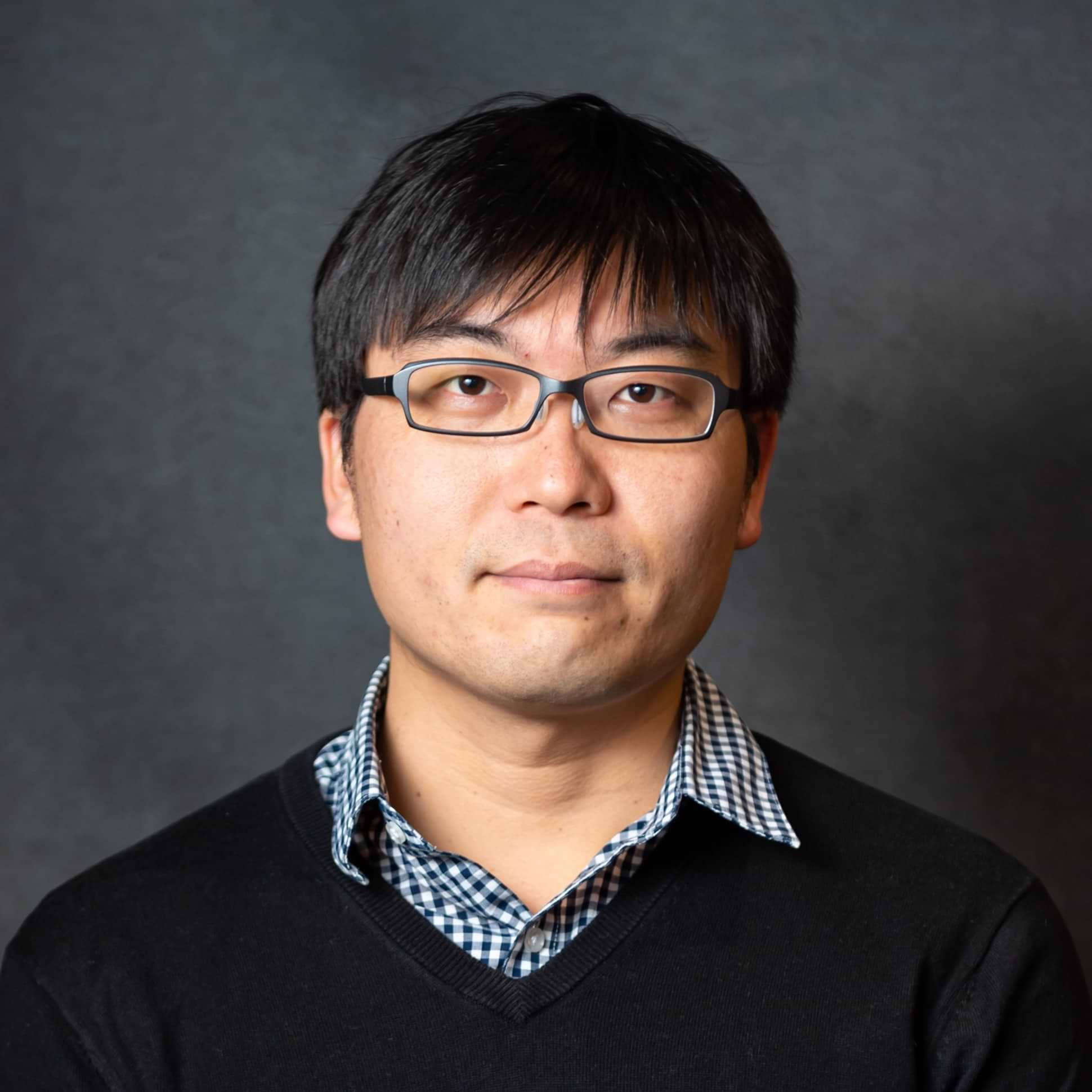

Fukui: At Japan Post, to use my favorite soccer analogy, I was dedicated to the number 10 position (playmaker). Since joining Tokyu, I've spent nearly two years in a position akin to the number 6 (defensive midfielder) – operating behind the number 10, handling everything skillfully and all-around.

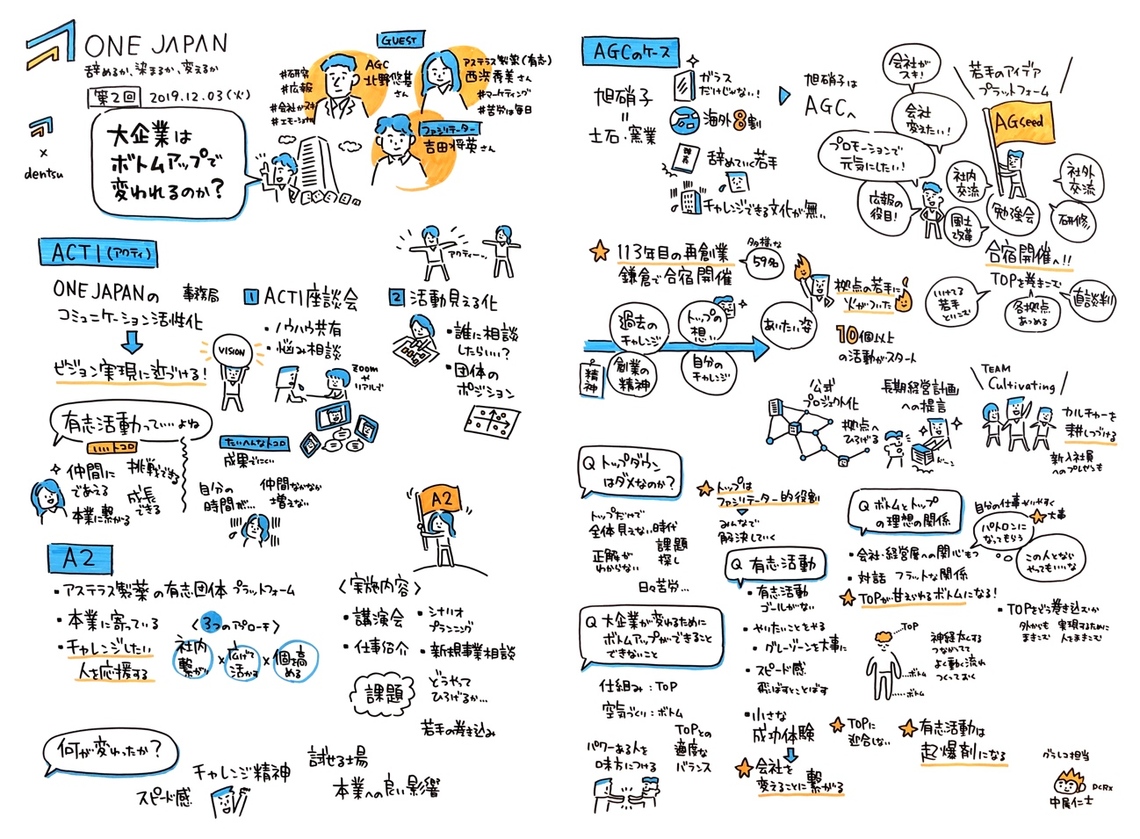

I believe this applies not only to roles within a team but also to the role of teams within a company. Open innovation activities, like accelerator programs, should fundamentally be positioned as a means to achieve management goals aligned with the company-wide strategy. However, recently, there are cases where operating accelerator programs or CVCs (Corporate Venture Capital) has become an end in itself.

Therefore, I am also conscious of first establishing open innovation that aligns with the company's overall management strategy. It's not just about leading as the playmaker; it's also about gently correcting the course when I sense such misalignment.

Yoshida: I see. In Japan, innovation-minded people often aspire to be like Sakamoto Ryoma, but what's truly needed is someone like Katsu Kaishu. A midfield-type role that unifies differing interests. Ryoma was ultimately assassinated, leaving no one to replace him. In that sense, perhaps it's crucial for companies not to personalize the revolutionary figure to a single individual, but to leave behind an "ism" within the organization.

Fukui: I agree completely. Ultimately, I want to create a universal success model for generating innovation within large corporations. The initiatives I'm pursuing at Tokyu are challenges aimed at realizing that goal.

Regarding Tokyu's Accelerate Program, I see it unfolding in three phases: Phase 1 (2015-2017) was the founding and position-establishing phase before I joined; Phase 2 (2018-2019) focused on organization and systemization through measures like year-round applications; and Phase 3 (starting 2020) is the democratization phase, expanding this as an option to a broader range of people within the group. Honestly, I came to see it this way because of my current experience—acting while thinking about "how the organization can accumulate strength," rather than clinging to the role of a command tower.

To be self-critical, there's a tendency for corporate intrapreneurs in large companies to be fawned over even when they don't deliver results like revenue or profit contributions typical of startups. This leads to an organization dependent on specific innovators and unable to generate innovation as a team. Short-term, that might be acceptable. But to truly transform an organization, you need to hire new talent or scale up teams to leverage their impact. Otherwise, you'll forever remain stuck in the same phase of efforts.

Yoshida: People who start their own businesses and those who climb the corporate ladder within large companies have different natures, right? Striking that balance allows for innovation that could never happen without the foundation of a large corporation, driven by employees with an entrepreneurial spirit. As someone belonging to a large corporation myself, I understand that mindset.

Fukui: To use another soccer analogy, since joining Tokyu, I feel I've gained the perspective of watching the field from directly above. I've become more conscious of thinking about how to ensure passes reach their intended targets and filling positions left vacant. It's like playing different roles – sometimes midfield, sometimes playmaker.

However, I keenly realized over these nearly two years that staying away from the playmaker role (number 10) for too long dulls your instincts. Sometimes you need to consciously push forward yourself. It's all about balance. Because of this, for about a year now, while running the Accelerate Program, I've also been preparing as the lead person for a separate open innovation initiative. My current department often forms teams on a project basis, so I'm currently playing both the number 10 and the number 6 roles. Also, in this era, with remote environments and IT tools well-established, enabling various possibilities, I think it's also valid to, for example, act as a coordinator within the company while simultaneously advancing a number 10-style project in an extracurricular activity like ONE JAPAN.

Yoshida: Maintaining versatility is crucial—both for preserving your capabilities and showcasing your diversity to others. But what about those who can't become versatile utility players like you, Mr. Fukui?

Fukui: Being a leader doesn't mean you have to be a utility player yourself. I think it's crucial to have utility players on your team who can bring out your strengths.

What Large Corporations Can Offer

Yoshida: Earlier we touched on extracurricular activities. Values are shifting now, with individual strength and presence growing stronger. I'll ask directly: even so, is the existence of large corporations still necessary?

Fukui: I believe there are things only large corporations can do. This is especially true for companies like Japan Post or Tokyu, which serve as infrastructure supporting people's daily lives. Furthermore, individuals can shine precisely because there is a corporate foundation.

Simultaneously, it's precisely because these shining individuals exist that the foundation thrives. I feel it's not a binary choice where one is better than the other; the balance where individuals and the organization mutually support each other is crucial. Within a large corporation, you can gain the satisfaction of working with a sense of community while also enabling diverse ways of working. Achieving that balance would be ideal, wouldn't it?

Yoshida: Dentsu Inc. is a case in point. Large corporations allow for large-scale challenges while also enabling personal pursuits outside the company. While starting a business or joining a startup are options, taking action within a large corporation might also be a path to building a career that, in a way, "has the best of both worlds."