Titled "Quit, Conform, or Change," this series explores the new "potential of large corporations" through dialogues on themes surrounding corporate transformation. Starting with the third installment, we will examine case studies of large corporations challenging transformation, selected from companies affiliated with ONE JAPAN's volunteer groups. We will interview the individuals involved to consider the "potential of large corporations."

ONE JAPAN: A practical community gathering corporate volunteer groups centered around young and mid-career employees of large corporations

Following the previous installment, Masahide Yoshida, a member of Dentsu Inc. Youth Research Department and a ONE JAPAN affiliate, spoke with Takahiro Suzuki and Yusuke Doi (Representative of ONE JAPAN TOKAI), who oversee Toyota Motor Corporation's internal volunteer business contest, the "A-1 CONTEST."

Why are "unsuitable bosses" valued by companies?

Yoshida: How did the "A-1 CONTEST" business contest you launched within Toyota, and the company-wide open call "B-PROJECT" that emerged as a result, impact your individual careers?

Doi: Through these two activities, I began pursuing a career path focused on launching new ventures within the company. My current assignment to Alpha Drive—a venture with six members and no capital ties—was made possible because I gained understanding from various internal stakeholders connected through A-1 CONTEST and B-PROJECT, including HR and executives. This allowed me to lay the groundwork before consulting my direct supervisor.

Suzuki: I think Doi's ability to "spread his furoshiki" and communicate broadly is unique within the company. Perhaps due to his experience with ONE JAPAN and student organizations, his sense of community boundaries differs from most people. He doesn't see walls or fences, but rather lines drawn on the ground, and he boldly crosses those boundaries—or rather, enters easily. So, he might sometimes be misunderstood, but I'm sure he doesn't mind (laughs).

Yoshida: I'm also not good at easily approaching strangers. That's precisely why I honed my strength in youth research and improved what Suzuki-san mentioned earlier: "the ability to be approached." Rather than viewing people above or beside you in the organizational pyramid as rivals or enemies, what matters is how much you can make them find you interesting.

Doi: That kind of collaboration would be great for incorporating examples from pioneers within the company. While there's knowledge that can flow from the bottom up, I personally get "hints for avoiding the pitfalls" by building good relationships with the older generation. My seniors also tell me things like, "If you do this, you'll fall into this trap," sharing their own experiences of becoming the "dead bodies" (laughs).

Yoshida: I see. The moment you think, "I won't become like that senior," you end up dismissing their good points and what you could learn from them.

Suzuki: It's tricky to get the balance right here, but I consciously avoid becoming the kind of person who seems perfectly balanced and polished to my superiors. Especially when you're young, there's motivation in wanting to prove them wrong, so I think it's good to assert your own ideas.

Even if you have a boss you don't get along with, analyzing them and asking "Why does the company value them anyway?" is a better approach. That might be the lesson to learn.

Is "being well-liked by juniors" a skill?

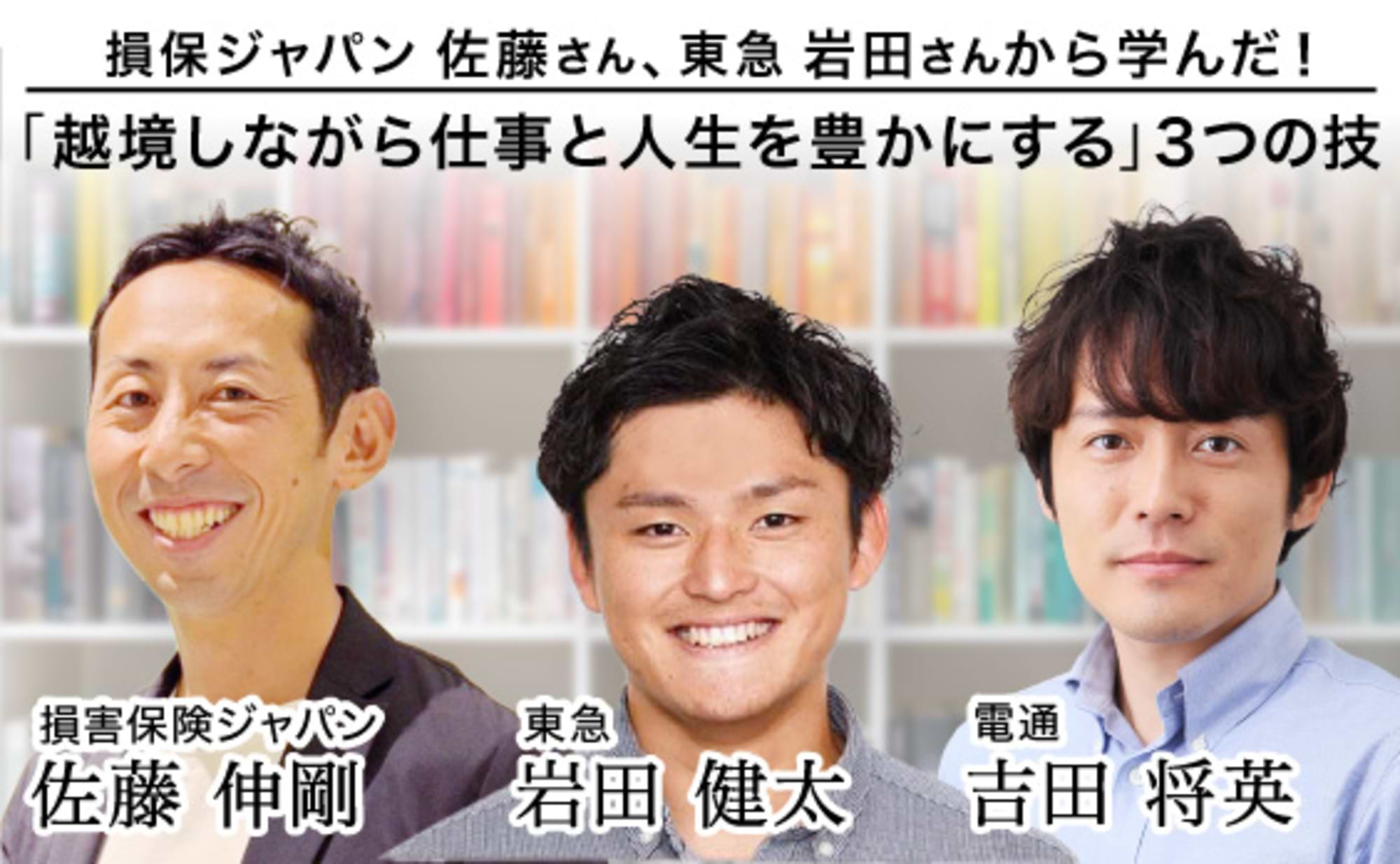

Yoshida: Suzuki-san, you're not just someone who can win over superiors; you're also part of a generation now in mid-career with more juniors reporting to you. Do you have any approaches for good relationships with juniors, or ways to help them "step over your shoulders"?

Suzuki: I usually distill my experiences and share them, hoping they'll surpass me faster. Personally, I believe experience isn't about refining what's right, but about increasing your options. Ultimately, they should decide and act for themselves, but "having the older generation's experience become the younger generation's options" is good for the organization. For seniors, it also trains us to speak without sounding like we're bragging or trying to show off.

Yoshida: There's also the term "upward pressure from below." For seniors, hierarchical relationships have negative aspects too—like perceiving juniors as threats, worrying about miscommunication, or fearing backbiting. What's the first step toward adopting an open attitude?

Suzuki: What I consciously focus on is not fixating on being the one who teaches.

When experiencing culture shock from younger people, it's easy to think "I don't understand them" and create a divide yourself. Of course, juniors sometimes teach me things too. Even if I can compete with them technically, I know I can't win in terms of speed or momentum.

Yoshida: Generally, since older people tend to know more, the structure often becomes seniors teaching juniors. But hearing Suzuki-san's words makes me think it might just be that the types of knowledge are different.

It's true that seniors know workplace etiquette, but younger people often understand how to perceive the world in line with current trends. So fundamentally, we should be cooperating to reach new frontiers together. Since younger people keep increasing every year, lacking this mentality risks accelerating your own aging.

Suzuki: Some people can keep putting in overwhelming effort like they did when they were young, no matter their age. But if you think, "I need to utilize the younger generation's strengths too..." then you need to be conscious of how you interact with them. It's important to have that "ability to be cherished" as a senior, or to let juniors tease you a bit.

Doi: Speaking from a junior's perspective, I consider Suzuki a best buddy (laughs). Seeing how Suzuki interacts with older generations, I know he accepts "teasing from below." That said, it's not just about being friendly; he properly corrects us when we're wrong as a senior should.

For example, Toyota has this internal culture called the "A3 culture," where reports are made on a single A3 sheet of paper. At the start of training, I couldn't grasp its value, but Suzuki "translated" its meaning and usefulness for me. Now I totally get it (laughs). Maybe because he's not a direct superior but more like a "slightly above" mentor, he doesn't nitpick or nitpick. Instead, he gives guidance that points us in the same direction.

Will you make them repeat the same mistakes, or will you make them overcome the obstacles?

Yoshida: Observing various senior figures, I see two types: those who want juniors to experience the same hardships they endured, and those who aim to break the cycle in their own generation. I feel Suzuki-san is the latter type.

Companies like Toyota have social significance. In the sense that employees can improve society by improving the company, getting junior employees to learn quickly makes sense not just for the company but for society as a whole.

Suzuki: Exactly. From a global perspective, I don't think Japan can afford to be fighting amongst ourselves internally right now.

Yoshida: I think your recognition that it's natural to give juniors shortcuts in a positive sense stems from this very understanding.

Doi: Incidentally, whenever this topic comes up, the phrase "stepping over corpses" keeps surfacing. But in reality, seniors within an organization aren't corpses; they're people running ahead of us. Their very presence makes us realize we must learn. Taking a broader view, seniors themselves stand on the shoulders of their own seniors. If the organization's direction is aligned, knowledge should accumulate steadily. Conversely, if everyone's heading in different directions, it becomes a world of personal likes and dislikes, and the strengths of tradition and large organizations are lost.

Suzuki: Personal preferences certainly have irrational aspects, but if they lead to positive outcomes—like acting with human warmth—then I think they're actually beneficial. I believe human relationships within an organization should have a foundation of warmth, upon which rationality is built. Rationality built on a cold foundation tends to struggle. Even in the A-1 Contest, we remind our operational members, "Don't forget that participants are submitting entries outside of their work hours."

Yoshida: I see. Work often seems more efficient and moves faster when handled dryly. People who are wetter are easily labeled "too nice" or "soft." But you're saying there's intention and purpose behind being wetter. It's true that few people consciously recognize this.

While we intellectually grasp the importance of "being likable" as a senior colleague, like the relationship between Suzuki and Doi, pride or organizational culture can make it difficult to emulate. Yet, it doesn't seem like a skill only a handful of supermen can master. It would be great if it could be adopted as a practical "skill" for thriving within an organization.

It's not just about getting along with older or younger generations; it's about recognizing that working in a large corporation offers opportunities to refine your approach to the workplace. This new way of being a senior or junior colleague should improve companies, ultimately contributing to a better society and enhancing Japan's competitiveness.