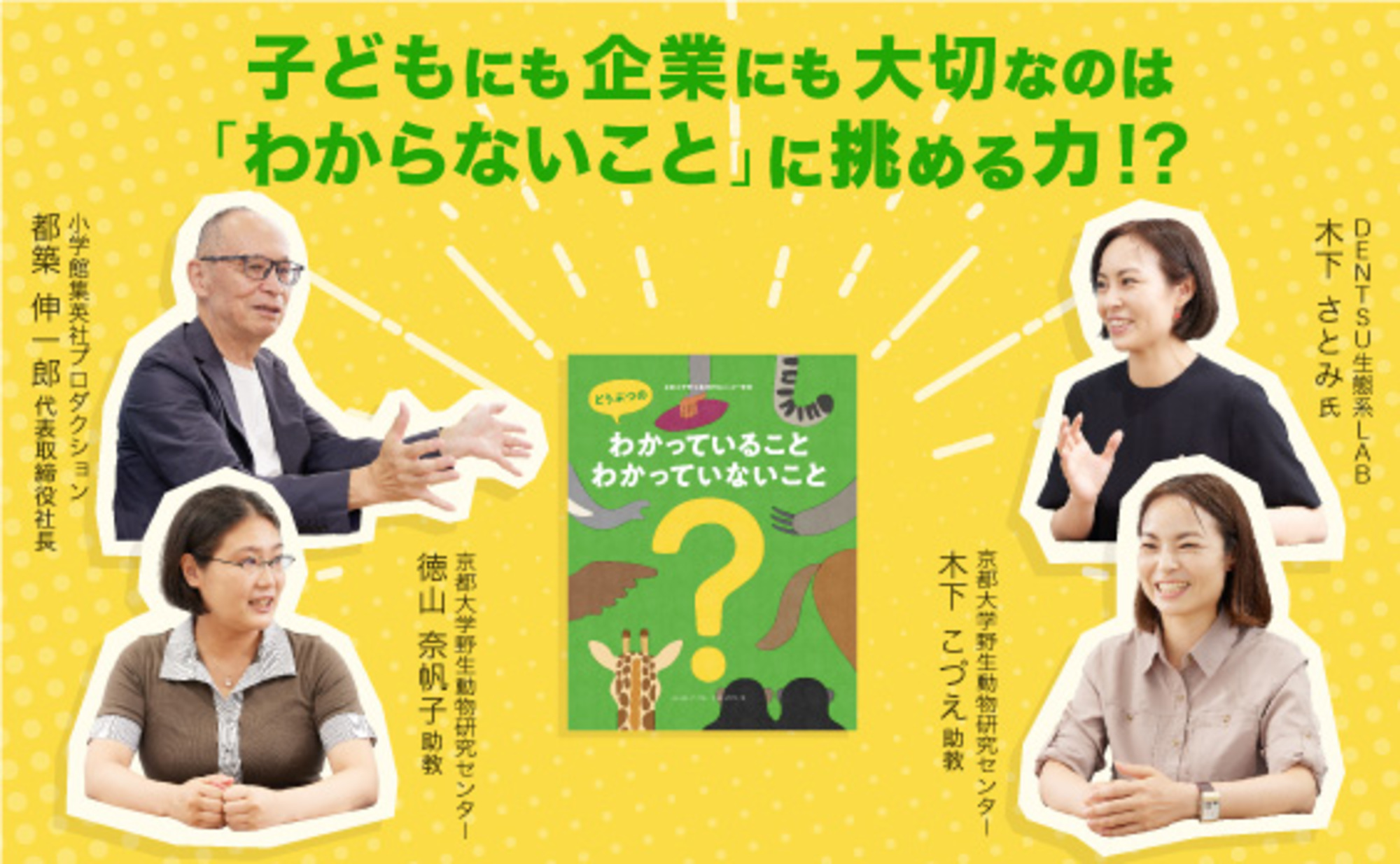

The DENTSU Ecosystem LAB confronts various challenges related to ecosystem conservation and considers communication strategies for solving them. In June 2024, the second installment of the picture book series, "What We Know and Don't Know About Dinosaurs," was published. This book was planned and produced by LAB members Satomi Kinoshita and Taisuke Yoshimori, with "exploration" as its theme ( release here).

Following the article published upon the first volume's release, this time features a tripartite discussion between Ms. Kinoshita, Mr. Yoshimori, and Dr. Makoto Manabe, Deputy Director of the National Museum of Nature and Science and a dinosaur researcher/paleontologist who supervised the picture book. They exchanged views on the behind-the-scenes of the second volume's production, the approach to "inquiry" in paleontology—where hypotheses about "what we don't know" are formed and elucidated from limited data—and how to apply this mindset in business.

From left: Satomi Kinoshita, Dr. Makoto Manabe, Taisuke Yoshimori

We hope more children will feel excited about situations filled with unknowns

—First, could you tell us how the decision to create the second picture book came about, and why you chose "dinosaurs" as the theme?

Kinoshita: We originally intended to create a series from the first book's publication. We initially considered "space" for this theme, but during our research, the "unknowns" we encountered felt too vast—perhaps only suitable for a final chapter? Meanwhile, through another project, we connected with Professor Manabe, and the "dinosaurs" idea emerged.

Yoshimori: Since it's a picture book, the key point was whether the theme would capture children's interest. The first installment, "Animals," featured creatures many children already knew, and they could visit zoos after reading the book. Considering a sequel, we felt a theme slightly more accessible than space would be better. The dinosaur idea emerged as visually appealing to children, and we felt it was a great theme likely to spark their interest, so the discussion progressed.

——Professor Manabe, what made you decide to take on the role of supervisor for this project? Could you share what appealed to you?

Manabe: First, I was very drawn to the theme of "what we know and what we don't know." Whether it's encyclopedias or dinosaur books, the focus today is mainly on conveying "what we know." In reality, there are mountains of things we don't know about dinosaurs, but when communicating through books, the focus always ends up being on what we do know. The idea of highlighting "what we don't know" felt very innovative; I don't think there's ever been an attempt like this in a picture book before.

Another point: I've actually sensed a shift in society for about 15 years now. During Q&A sessions at lectures, I often get questions from children who want to become paleontologists. Around that time, I started hearing this question nationwide: "When I fulfill my dream and become a paleontologist, will there still be research left to do?"

I suspect the background to this is that while in the past, it was enough to simply say "what you wanted to be in the future," today schools seem to encourage children to research things like "what kind of effort is needed to get that job" or "how much future potential does it have?" As they research, some children start worrying unnecessarily. I wanted more children and readers to feel excited about the fact that "there are so many things we don't know."

——Conveying the "unknown" has become crucial, especially given the situation of children today.

Manabe: Exactly. While you can find plenty of known facts online today, the unknowns rarely make it into academic papers. Whether it's dinosaurs or plants and animals, science is a field where researchers worldwide have been studying desperately for hundreds of years, and yet there are mountains of things we still don't understand. Researchers are people who investigate and study precisely to uncover even a little more of that.

Noticing what we don't know, or trying experiments to understand things a little better yourself, is the first step toward becoming a researcher. I thought this project could convey that message too.

Colors and forms are mostly imagined? Dinosaurs are creatures where the "unknown" far outweighs the known.

——I imagine the key point for this picture book was deciding which types of dinosaurs to feature and what "known facts" and "unknown facts" to include for each. How did the production process proceed?

Kinoshita: First, we conducted three or four lengthy interviews with Professor Manabe and Professor Takahiro Tsuihiji, who also researches evolutionary paleontology at the National Museum of Nature and Science. We prepared many questions beforehand, but once we met, the conversation became incredibly deep right from the first question... (laughs). We didn't limit ourselves to specific dinosaur types. As we talked about various things, sometimes flipping through encyclopedias to ask about points that caught our interest, we determined the balance of dinosaurs to feature, such as the ratio of carnivores to herbivores. Then, we pieced together the order of themes like a puzzle, aiming for the reader's world to expand as they read, ultimately connecting the story back to themselves.

——Could you tell us about any particular aspects you focused on when presenting it as a picture book?

Kinoshita: While listening to the story, as the writer, I felt I needed to be careful about how I used the word "evolution." Some people might think that creatures that evolved are more amazing or superior, but evolution is simply when a feature that happened by chance through mutation happened to be suited to the environment at that time. It's not that they're great because they evolved and survived, nor is a larger body necessarily better. I tried to show a wide range of features, like how this dinosaur is small so it can move easily, and write about the strengths of various creatures.

——Professor Manabe, were there any particular points you focused on or took care with during your supervision?

Manabe: My main request was to "include as many famous dinosaurs as possible." Since this is a picture book for children, I wanted to cover the major lineages comprehensively, ensuring no major group was completely absent.

The biggest challenge was that for dinosaurs, what we don't know far outweighs what we do know. It's mostly a case of "we know this much, but beyond this point, we don't know." Research involves finding out "what we don't know," forming hypotheses, and then testing those hypotheses. So, researchers each have their own ideas and hypotheses. For this picture book, I didn't want to focus on whose theory seems most correct right now. Instead, I wanted the message to be, "We don't know this now, but hopefully we will in the future." I struggled a lot with how to express that point.

——What perspective did you take, Yoshimori-san, as you expressed this through illustrations?

Yoshimori: Honestly, hearing Professor Manabe speak was the first time I realized that the shapes and colors of dinosaurs depicted in picture books are mostly the artist's imagination. Half of me was confused, thinking "What do I do now?" and the other half thought, "Oh, that means I can freely imagine and draw them however I want!" (laughs).

——That's true. Fossils are basically just bones, after all.

Yoshimori: Exactly. Unless the tissue structure that reveals color remains on feathers or scales, we can't know the precise color or pattern. To analyze that, you'd have to cut the fossil into tiny pieces, so it's difficult to use every discovered fossil as a sample just for color identification. Since only about ten species have color-bearing tissues preserved in fossils, illustrators apparently use their imagination to depict colors and patterns, factoring in information like habitat and ecology. So, I also looked at various dinosaur pictures and encyclopedias while drawing this illustration.

Kinoshita: Regarding the illustrations, the discussion about "teeth" was fascinating. Carnivorous dinosaurs are often depicted with visible teeth, but it's possible that when their mouths were closed, their teeth weren't actually exposed. Visible teeth look cooler and more carnivorous dinosaur-like, so there was a consideration between that artistic expression and the hypothesis.

Yoshimori: If you don't draw teeth, they all just look like cute lizards (laughs). So, when drawing species meant to embody "THE Carnivorous Dinosaur!" image, you really have to show them off boldly to get that impact... We adjusted while keeping that point in mind.

The approach itself—experimenting without deciding what's correct, embracing the "unknown"—is what matters.

——Even in our work, there are countless unknowns. I feel the ability to identify these unknowns and devise ways to address them is increasingly demanded of both children and adults. Professor Manabe, who explores creatures we can no longer see based on limited materials like fossils, what kind of thought process do you employ?

Manabe: As you mentioned, dinosaurs mostly leave behind only hard parts like bones and teeth. Typically, 80-90% of an organism's body consists of soft tissues like muscles. So, bones and teeth alone provide information on only about 10% of the total body weight.

We basically look at that 10% of information and, through comparing many fossils, deduce things like, "This bone shape is a feature unique to this group." If this part of the bone has a depression or a ridge, we infer that muscles must have attached to move this joint. Based on the depth of the depression, we estimate the amount of muscle and how it moved—for example, that the muscles for bending the arm were highly developed.

Manabe: Furthermore, we compare them to modern creatures. Since dinosaurs are reptiles, we compare the muscle attachments and body structure to crocodiles and turtles. But we also compare them to modern birds. Why? Because some dinosaurs didn't go extinct; they evolved into birds. So birds share the closest DNA.

The information right in front of us—observing fossils—is important, but comparing them to modern reptiles and birds is equally crucial. Therefore, we also need to study the muscles and nerves of modern creatures through dissection and other methods. We repeatedly use an approach that gradually "sandwiches" dinosaurs between research on their reptilian ancestors and their avian descendants.

——So you consider various possibilities, studying even seemingly unrelated fields, then synthesize them.

Manabe: Unlike fields like chemistry, biology often can't rely on straightforward "experiments." Within that constraint, we write papers explaining, "Based on this data and this interpretation, we can infer the dinosaur's form and ecology was like this." To do that, we use evidence like, "If it were a bird, it would use its muscles this way," or "If a crocodile had this feature, it would move like this." To make our hypotheses convincing, it's crucial to build upon diverse data.

Yoshimori: What I found fascinating while making the picture book was how researchers interpret the same evidence completely differently. People inherently see evidence differently. That situation is similar to our everyday work, where it's about how we interpret the conditions and data presented to us.

A major theme of this book is "Hypothesis and Imagination." "Knowing" something and "understanding" it, "not knowing" something and "not understanding" it—they seem similar, but are actually completely different. You can research what you don't know, but you can't research what you don't understand. So you have to imagine, and furthermore, whether that imagination is correct, and when you might understand it—no one knows. Work is probably the same; you don't immediately know if your thoughts or approach will ultimately succeed.

Hearing Professor Manabe's perspective while creating the picture book gave me this viewpoint, which was incredibly interesting.

——Researchers can formulate various hypotheses and take diverse approaches. Hearing you speak now, I feel that the "approach to the unknown" itself is important—trying things without deciding what the correct answer is.

Yoshimori: In this era, information is overwhelmingly abundant. Knowing information beforehand makes us feel like we understand, but back when that information didn't exist, we could only imagine. Now, conversely, I feel the scope of that "imagination" has narrowed.

For example, if you're given conditions and need to derive an answer from what's already known, AI is overwhelmingly faster. But freely imagining beyond what's unknown, based on certain conditions? That's difficult for AI. That kind of "imagination" is probably something only humans can do, and I think the breadth of such hypotheses is what we need right now. Perhaps the only area where humans can expand our future enjoyment is through imagination. I believe that "what we don't know" is what fuels the expansion of that imagination.

Kinoshita: Even when looking at the same bone, the amount Professor Manabe imagines from it is different, right? Also, personally, I felt curiosity is important too. For example, we heard stories about people who went down different paths in engineering or physics somehow connecting to the path of dinosaurs at some point.

Yoshimori: Right. I heard about a researcher who approached the running speed of Tyrannosaurus from a physics perspective. That kind of "detour" can lead to dinosaurs too. It was really fascinating.

Kinoshita: With curiosity, you can notice small triggers and approach things from various angles. Furthermore, even if you give up and take a different path, when you eventually return, synergistic effects can open new avenues. That story really emphasized how important that is.

The importance of a "space" where you can "observe" from various angles and share opinions and impressions

——Both picture books and museums seem to spark curiosity. Earlier we discussed "hypotheses" and "imagination," but one advantage of museums is enabling the "observation" of materials needed in the preliminary stages. Could you share your thoughts on the importance of "observation" in inquiry-based learning and how museums can be leveraged for this purpose?

Manabe: Today, with the internet's development, information like 3D-animated fossil data is publicly available, making information gathering easier than before. However, seeing the complex shapes and skeletons of actual fossils right before your eyes, examining them from various angles, is something only possible in places like museums.

Simultaneously, as researchers, displaying findings from excavations and studies allows us to hear diverse reactions from visitors—comments like "It's huge!" or "Surprisingly small!"—which is a significant benefit. Often, during these conversations, visitors ask questions like "Could this mean...?" that researchers hadn't even considered. The ability to share such a wealth of opinions and impressions with many people, providing both the "space" and the opportunity for this exchange, is a major strength of museums.

——Mr. Kinoshita, how do you envision this picture book being used?

Kinoshita: For children, I'd be delighted if this book sparks their interest in various things and inspires future researchers. Even if they don't become researchers, I hope they grow into adults with that perspective. At the same time, I really want adults to read it too.

We operate under the name DENTSU Ecosystem LAB, and we are in a situation where we must advance biodiversity and ecosystem conservation as we approach the milestones of 2030 and 2050. Short-term goals play a vital role in driving corporate and societal change, but viewed from the opposite perspective or over the long term, they can sometimes lead to destruction. Therefore, I hope that through these picture books, we can offer a perspective that encourages taking a "detour" – constantly questioning whether this is truly the right answer, and considering whether hints might lie in places we haven't yet noticed. This requires maintaining a long-term viewpoint simultaneously.