I had done this kind of work before Fukuoka—immersing myself in a place to find marketing insights. The mission was: "Report on the food culture for companies expanding into Nagoya."

I was born and raised in Tokyo. All my relatives are Giants fans. I saw Sadaharu Oh hit his world record home run at Korakuen Stadium, and in kindergarten, I even wrestled with Shigeo Nagashima. Yet, because of a single card that came as a prize with a snack, I've been a Dragons fan ever since I can remember. Nagoya was, in a way, my "dream destination."

Chicken wings and curry udon. Taiwan ramen and hitsumabushi.

Napolitan spaghetti served on a sizzling hot iron plate topped with a sunny-side-up egg (commonly called "Italian"). Chawanmushi with lunch sushi. Mayonnaise on chilled Chinese noodles. Come to think of it, boiled eggs are even part of the morning set at coffee shops. "How much do they love eggs?" "Huh? Do people in Nagoya think it's a bargain when something comes with an egg?"

The "Mirakan" (*1) spaghetti with thick sauce, which I'd heard about, was a classic spaghetti style, distinct from today's al dente pasta culture. Even though it was my first time trying it, it had a nostalgic flavor, somewhat reminiscent of Napolitan. Bread bought at the convenience store had margarine and sweet red bean paste. "Is Nagoya's food culture justアレンジメニュー (arranged menu) made in coffee shop kitchens?"

Miso katsu, dote rice, miso-simmered udon. Even in Chinese food, miso-based dishes like twice-cooked pork are popular. "So it all comes back to Hatcho miso?"

Other observations: "Shops close early at night, huh?" "Seems like it's all carbs, huh?" "Strong local pride, huh?" Immersing myself in the moment, I recorded various information without judgment, jotting down every fleeting sensation as it arose.

This is a method called "ethnography." Ethno- means "ethnic group," and -graphy means "description." It's an approach in cultural anthropology to unravel the behavioral patterns of a specific group. A famous work in this field is 'An Ethnography of Bōsōzoku'. The author, scholar Ikuya Sato, participated in observing the " Bōsōzoku" ethnic group and revealed their reality ethnographically.

Such qualitative research methods inherently help capture valuable nuances that quantitative surveys and numerical analysis tend to strip away. That's likely why "ethnography" has been a major topic in the business world these past few years. However, the reason it seems poised to fade as a passing fad might be that many people consume it too easily as just another "trend." Getting swept up by buzzwords is truly futile, isn't it?

But enough digressions.

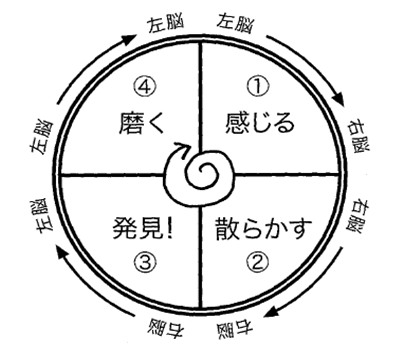

When I attended a lecture by Mr. Dai Tamura, Director of the University of Tokyo Innovation School, he mentioned that "in the process of creating innovation, the time spent on ethnography can amount to as much as 70% of the total." I believe the energy required for the "feeling mode" of gathering material for ideas is precisely that significant.

James W. Young, a veteran of the advertising world, wrote in his 1940 book: "The first stage (of creating ideas) is gathering material. You will no doubt be surprised that this is nothing more than a simple and obvious truth. Nevertheless, it is equally surprising how often this first stage is ignored in practice."

Honestly, whether you call it "feeling mode," "ethnography," or "data collection" doesn't really matter. What's crucial is thoroughly gathering that material as the first step in idea creation.

Well then. My favorite detour in Nagoya has gone on a bit too long. Next time, let's move on to "Scatter Mode."

Circular Thinking

Enjoy!

※1 Abbreviation for "Country" (vegetable topping), "Milanese" (meat topping), and "Milanese Country" (both toppings combined).

※2 Terms that appear to be plausible jargon at first glance but lack a clear definition (or are used regardless of any clear definition).