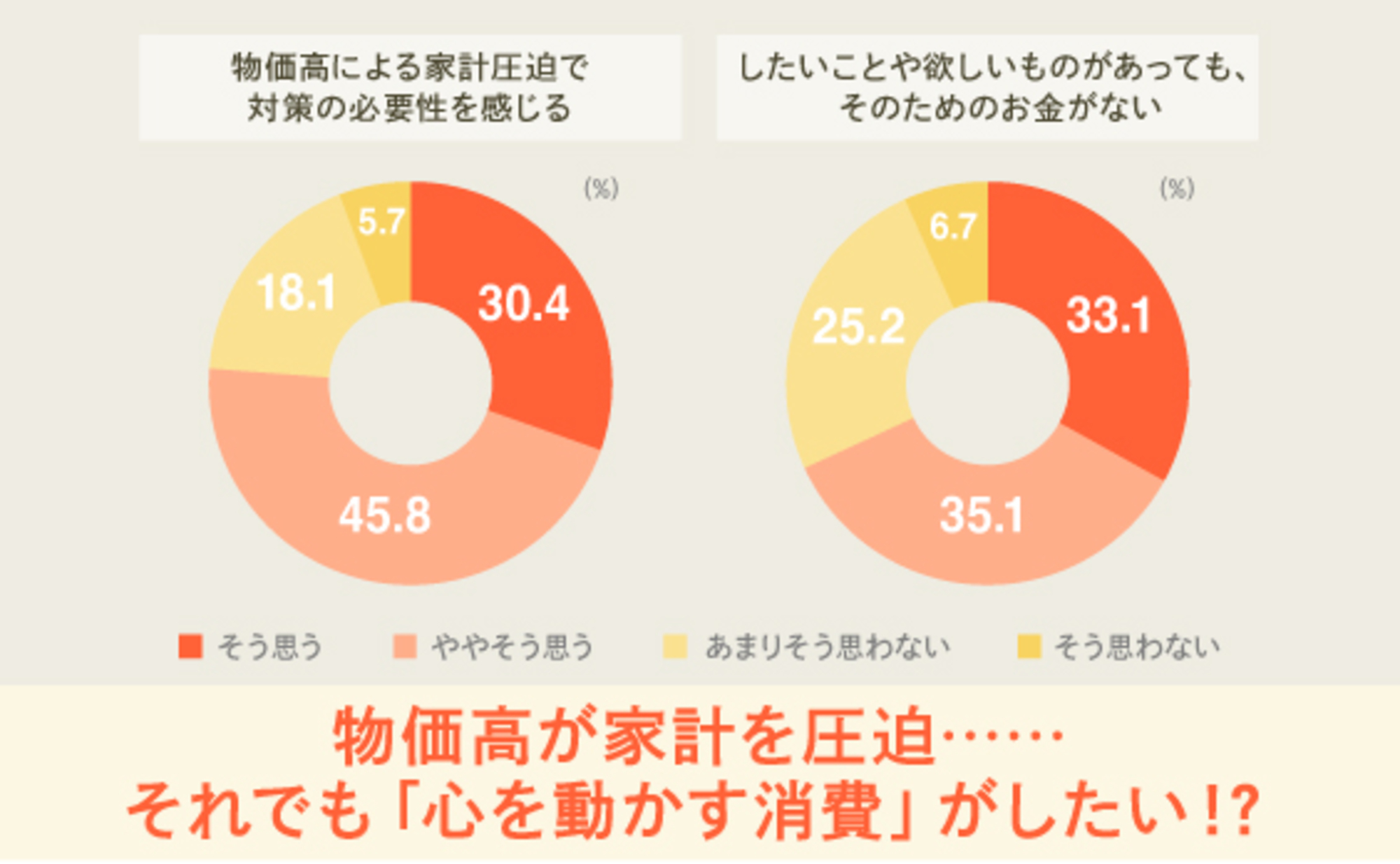

DENTSU DESIRE DESIGN (DDD) is a project that aims to uncover the modern consumer profile, which has become increasingly elusive to companies, by revisiting consumption consciousness rooted in "Desire."

DDD offers a "Heart-Moving New Product Development Program" aimed at "concretizing the 'desires' deep within customers' hearts and fulfilling them." This program accompanies new product development from the consumer's desire perspective, based on DDD's discovery of 11 new modern "desires" and the real voices of approximately 20,000 people compiled in its database from regularly conducted "Heart-Moving Consumption Surveys."

In August 2023, a product development project utilizing this program commenced at Chuo-ken Senbei, a century-old rice cracker shop celebrating its 100th anniversary. Following preliminary input and workshops involving DDD members, the new product "Dip-Style Rice Crackers" was born in just about 10 months.

This time, we held a roundtable discussion with Chuo-ken Senbei's product department members Mutsumi Kitaoka, Yoko Nishimura, and Yasuko Sato, who participated in the project, along with DDD's Tsunaki Fukui and Manabu Tachiki. They discussed the work undertaken during the project, insights gained through the workshops, and personal changes experienced.

■For details on the project's background and introduction, please see here

From left: Mr. Tachiki and Mr. Fukui of DDD; Mr. Kitaoka, Ms. Nishimura, and Ms. Sato of Chuo-ken Senbei

Product development that "works backward" from consumer insights, starting with modern "11 new desires"

Tachiki: We collaborated on this "Heart-Moving New Product Development Program" based on the "11 Desires." First, having participated, could you share how you felt it differed from your company's previous product development methods and processes?

Kitaoka: Previously, our company focused on "things" when gathering new product information and designing concepts. We primarily sell rice crackers targeted at the gift market, such as for presents. Within that context, we analyzed competitors, market conditions, and popular products, adding originality as a value proposition.

While our own marketing efforts allowed us to visualize customer purchasing behavior, we couldn't see insights like "why they wanted this product" and lacked that data. This time, by receiving raw consumer voices organized from the perspective of the "11 Desires," we feel we've established a new product development flow where we can reverse-engineer what customers truly want from those insights.

The 11 Desires* defined by DDD for the modern era. (As of the workshop date. Content reviewed in March 2024.

Release here )

Nishimura: As Kitaoka mentioned, our previous product development started from a narrow perspective—focused on what we wanted to offer customers. This meant pursuing our specialty rice crackers or proposing seasonal flavors based on sales feedback.

This time, starting from consumers' "desires" for product development meant beginning by considering "what feelings they want to satisfy" when purchasing a product. It was a completely different process from before, and it actually made us realize why we hadn't considered that point before.

Sato: Previously, when designing products, we often started with a largely defined target profile and direction already set. So, starting from scratch with brainstorming ideas and developing the product's substance ourselves was truly fresh and an exciting approach.

Tachiki: Thank you. The common difference all three of you mentioned compared to previous approaches is that product development started by considering customers' true feelings based on the information and data provided by DDD. For this project, we first held preliminary study sessions led by DDD. After that, you read through a large volume of free answers (FA) extracted from the database—survey responses about feelings when their hearts were moved by consumption. How did you find the preparation before the workshop?

Sato: Reading through all the FAs was challenging, but at the same time, it was incredibly fun and I got hooked. Many responses resonated with me personally, making it very rewarding to read. It took time, but it was a valuable experience.

Tachiki: The number of responses for the "Heart-Moving Consumption Survey" has now exceeded 20,000 in total. Reading through them, it's fascinating to see things like people writing "excuses" for when they made a big purchase, or glimpses into their personalities.

In the subsequent workshop, participants grouped FA responses they brought based on similar underlying desires and assigned "desire hashtags." Then, using those hashtags, we envisioned target personas and states where their desires were fulfilled, leading to product ideas. Could you share your thoughts on the workshop?

Nishimura: What I found fascinating was how people interpreted the same response. For instance, regarding "I bought a dedicated stand to enjoy afternoon tea and felt fulfilled," one person read it as "This person must be the type who cares about every detail," while another pointed to the desire for recognition, suggesting "Maybe they want to be seen as stylish by inviting friends over and using the dedicated stand." Seeing the same response revealed how different desires emerge depending on the person interpreting it.

During the workshop brainstorming, having diverse members like Dentsu Inc. staff, our factory personnel, sales reps, and store staff meant we got perspectives beyond just "what we can do internally" – a limitation when only the product department thinks. It was incredibly fun discussing the "excitement" of buying new products and what truly moves people.

Data-driven, convincing target setting accelerates product development

Tachiki: Could you share any discoveries or learnings from running the program?

Kitaoka: With all the input we received, we were able to solidify our development direction based on which desires to focus on. Some aspects differed from the clusters we had imagined, and I believe that's where the real voices of consumers and the data were truly leveraged.

The direction set by examining such data, rather than relying solely on experience-based judgment, felt very convincing. At the same time, I believe that achieving this convincing target setting positively impacted the subsequent product development itself and its speed.

Tachiki: While this program was designed to help determine product development direction based on database information, I'm glad it was perceived as a truly novel approach.

Fukui: There was a lot of input beforehand, including how much to explain about the "11 Desires," so it might have been quite demanding for participants. Personally, I didn't think it was crucial to know exactly what each of the 11 desires entailed. My hope was that participants would engage in product development while considering what customers potentially desire and what it means for their hearts to be moved. I believe we successfully achieved that.

Sato: The naming of the "11 Desires" was particularly interesting. Phrases like "Desire for Unrestricted Freedom" or "Desire to Protect What Matters" used straightforward words that captured those "true feelings" that aren't easily expressed. Just seeing them brought the concepts to life. While the information volume was indeed substantial, each desire's essence was clear and resonated well.

Tachiki: While verbalizing "desires" is common, this naming was something we at DDD were particularly focused on. "The 11 Desires" took one to two months to create, so it's gratifying to hear that aspect was well-received.

This time, DDD members also participated in reading the FA and preparing workshop assignments, contributing their opinions. While we act as facilitators, we prioritized everyone approaching the workshop from the same perspective.

Fukui: Exactly. One goal was for everyone to hear our perspectives and realize, "It's okay to freely generate ideas without constraints." In this case, starting from the "desire" underlying feelings like " " or "I want to eat delicious rice crackers" ultimately led to generating a whopping 49 ideas.

The 'uncharted territory' we stepped into with Dentsu Inc. A high-stakes challenge became the catalyst for strengthening our collaboration.

Tachiki: From the 49 ideas generated in the workshop, "Dip-style Rice Crackers" were selected and entered the development phase. Development took place in a very short timeframe of less than six months from idea selection to launch. What were the most challenging aspects on the ground?

Nishimura: Ultimately, the options narrowed down to "Dip-able Rice Crackers" and "Soy Sauce, A Journey (tentative title)" using various soy sauces from across Japan. The debate over which to choose was extremely heated. Both sides were pressed to clearly state their "reasons," and I felt it was a product where making the decision itself required courage.

We ultimately chose the "dip-style rice cracker," but while we're experts in making rice crackers, developing dipping sauces is an entirely different field. We didn't even know where to start with development, and as a gift item, there was also the challenge of shelf life. It began with the fundamental question of which sauce maker to approach – it was truly uncharted territory.

Still, partnering with Dentsu Inc. gave us the courage to take that step forward. We unanimously decided: We want to create this new product! The fact we could challenge ourselves with an idea that had previously been rejected due to feasibility hurdles was significant in itself.

Tachiki: Calling it a new frontier might be an exaggeration, but we did manage to step into an expanded territory.

Nishimura: Yes. Once we started, we found enjoyment despite the uncertainties. Even with a tight schedule, we moved forward with the excitement of creating something new.

Sato: Regarding the schedule, every phase was critical, so we steeled ourselves and tackled it head-on. We developed not only the sauce but also the rice crackers, carefully considering shapes and textures that would make dipping easy. It was challenging, but it also became an opportunity to foster closer collaboration, including with our partner companies and factories. Building relationships where we could easily approach each other was truly valuable.

The key to achieving development in a short timeframe was role division and full participation in exchanging opinions.

Tachiki: After the development phase, Fukui and Takashi Chiba, also a DDD member, primarily supported the project. Could you share where you felt DDD was particularly helpful?

Nishimura: What stands out most was the advice on the product name. Initially, we considered stylish names like "Dip de Okaki" or "Dip Rice Bar." Chiba-san pointed out that a name should have a certain "discomfort" that catches the eye instantly in stores, while also immediately conveying what the product is. That led directly to "Dip-able Rice Crackers."

Regarding the schedule, you kept us in close contact and really pushed us forward. Even though we requested a demanding schedule, we still felt anxious. However, you created a framework that organized tasks by phase right from the start, which allowed us to proceed with confidence.

Fukui: Even when ideas emerge in workshops, many don't actually make it to productization. When you really commit to bringing something to market, the schedule becomes demanding, and delays are often inevitable.

Amidst this, Chuo-ken Senbei managed to progress to commercialization in under six months after the workshop. They did this without any compromise, advancing through processes like prototype production and packaging. I was impressed not only by their technical skill but also by their tremendous drive.

Kitaoka: Regarding how we managed the tight schedule, I think a major advantage was that we focused solely on the product development itself, leaving marketing and other aspects to the DDD team. If we had handled everything in-house, we couldn't have achieved this development speed.

Fukui: I think the key was maintaining clear communication while each party focused on their specific roles.

During development, we held weekly online meetings to exchange information and opinions. They even asked for our input on matters where we wondered if we should really be answering, making us feel like we were already part of the Chuo-ken Senbei team – we could speak freely without reservation. For us, it was a rare and invaluable experience to be so deeply involved and keep such close tabs on the situation during the development phase.

Nishimura: Indeed, internally, Sato and I focused on the product design and development itself, while Kitaoka primarily handled considering display methods for stores, sample creation, and promotion. However, everyone participated in the meetings, and we freely exchanged opinions without hesitation. We didn't just involve ourselves; we also engaged members from the Product Department, Sales Department, and Factory who participated in the workshops, asking for their support. We shared the situation at the monthly sales staff meetings held at the store, ensuring all project members were involved. We actively exchanged opinions using chat, and this method continues to this day.

Desires change with the times. We want to provide a new perspective that looks ahead over the long term.

Tachiki: After going through this entire initiative, have you noticed any changes in your own mindset or actions regarding product development?

Kitaoka: Previously, our thinking was product-centric, so promotional activities often focused on how to communicate functional benefits like "portability" to customers. Through participating in this project, I found myself thinking more about "what emotions we want customers to feel" and considering insights in that regard as well.

This was our first project with Dentsu Inc., and it was a significant experience to have them accompany us all the way to commercialization. We shared various elements, including our desire to incorporate new marketing processes and our aspiration to engage the entire company in product development.

Nishimura: I too have started prioritizing thinking about what emotions I want customers to feel when they buy the product. Why this product? Why this flavor? What underlying customer desire are we trying to fulfill? I'm now deeply focused on the customers themselves. It was also a valuable experience realizing that by collaborating with diverse people, we could achieve commercialization at this pace.

Looking back on the program, I can honestly say it was truly enjoyable. That enjoyment is a crucial element in product development. If we ourselves aren't having fun, we can't create products that delight customers. I'm glad that through our partnership with Dentsu Inc., we were able to create products where that enjoyment comes through to the customer.

Sato: In designing the contents, developing with a focus on how dipping changes the taste made me much more sensitive to flavor. Furthermore, I feel I thought more than ever before about how best to express the taste "in words" for any product. This was my first time developing products while discussing with others how to articulate their strengths. It's a perspective we'll need going forward, so I want to continue building on this experience. If we can pass this development approach on to our younger staff, it will become a real treasure for our company.

Fukui: For us, a significant aspect was not just brainstorming ideas in workshops, but being able to accompany the project all the way to commercialization. We were involved in product development, promotion, and received nearly full disclosure of information from everyone, engaging with all four Ps of marketing – Place and Price included.

What was especially appreciated was that this wasn't just positioned as a "fun new product," but as a core offering for Chuo-ken Senbei that could be built upon for the future. We hope to leverage this experience in new product development, branding, and marketing plans for other clients.

Tachiki: The current "11 Desires" were identified with a focus on the present era. Chuo-ken Senbei developed products at an incredible pace, allowing us to create something that leveraged that speed. However, depending on the product, some may enter the market in three, five, or even ten years. We are currently developing and testing methodologies to apply this approach to products that cannot be commercialized in short spans, such as automobiles.

Within Dentsu Inc., another project is discussing how the "11 Desires" might evolve in the future. The key going forward is how we integrate these insights with the "current era" we've captured. While we plan to continually review the "11 Desires" themselves to reflect changing times and consumer values, we also aim to create something with a slightly longer-term perspective. Thank you for your time today.