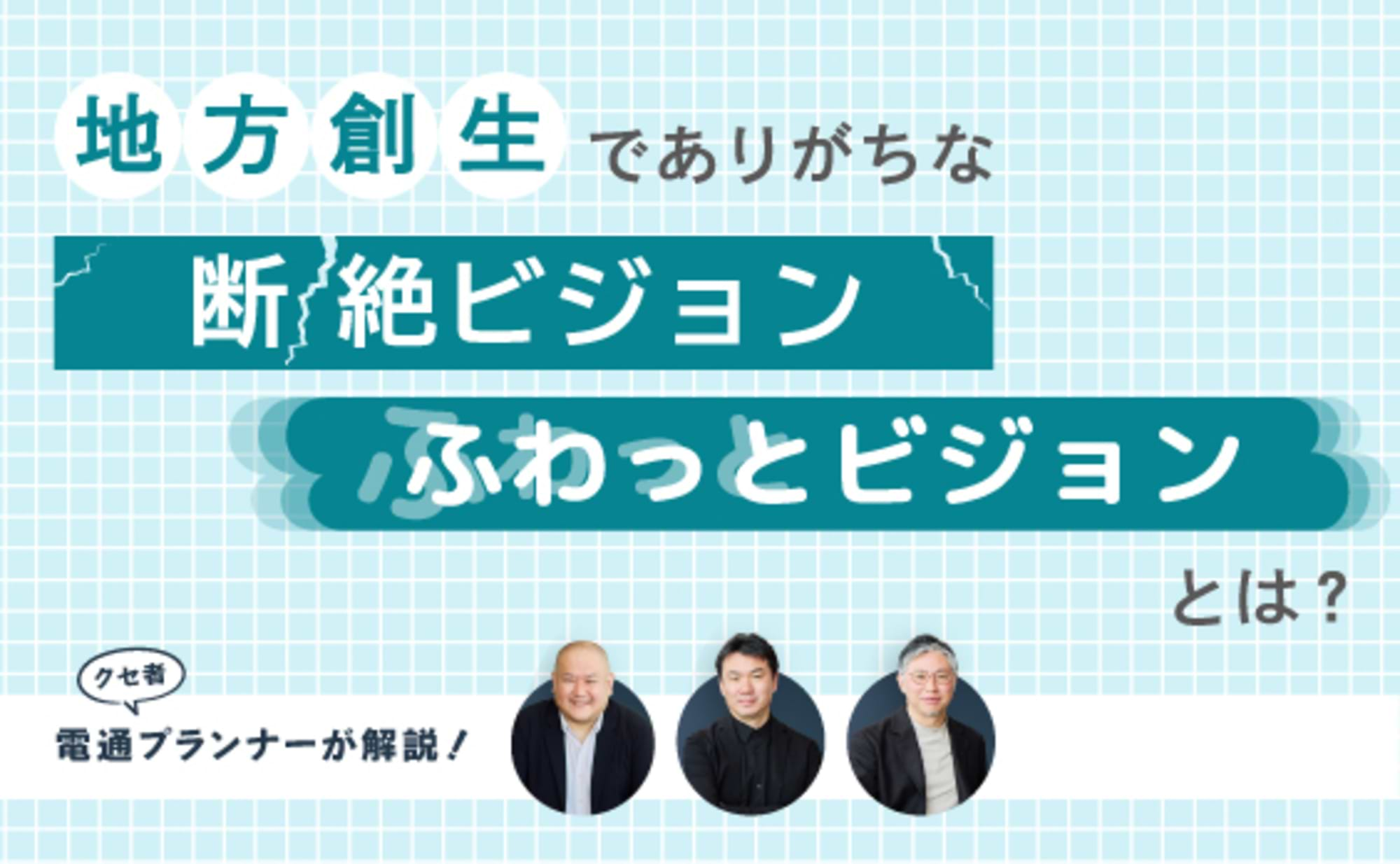

This series features insights from Dentsu Inc. planners with extensive experience in regional revitalization initiatives. In Part 1, we discussed the challenges of regional revitalization and proposed focusing on a region's "quirks" as a new approach to overcoming them.

The hypothesis is this: Couldn't the unconscious behavioral patterns existing within a region—its "quirks," so to speak—actually give the local economy and market its unique character and function as a "barrier" preventing the outflow of value to the outside?

That's the hypothesis.

That said, many readers might not immediately grasp this concept, so this time we'll introduce actual examples of these 'quirks' observed by Dentsu Inc. planners!

Presented by three "quirky experts": Toshiaki Morio of 47CLUB Inc., Takuya Kagata of Dentsu Consulting Inc., and Nobu Miyazaki of Dentsu BX Creative Center.

Regional quirks are "unconscious behavioral patterns"!?

Kagata: Starting this time, we'll discuss how to identify regional quirks. And how to leverage those identified quirks for regional revitalization through industries and tourism! But first, what exactly are regional quirks in a nutshell? If we just say "this region has this food culture," it becomes "how is that different from a local specialty?" right?

Morio: Food culture itself isn't a quirk. But if we focus on the background of "Why does this food culture exist?", we first find the "unconscious behavioral patterns" of the local people, and it's these unconscious patterns that nurture the food culture. However, "unconscious behavioral patterns" sounds stiff and is hard to grasp, so we use the more accessible term "the quirks of the region."

Miyazaki: We'll explain the details later, but our "Quirk Discovery" method within the "Quirk Model" we developed is as follows. It's a bit complicated, so just skim over it for now.

Miyazaki: Each region possesses unique behavioral patterns—quirks—that unconsciously influence its culture. These patterns develop against backgrounds like "natural environment," "economic environment," and "history."

These unconscious quirks shape distinctive regional outputs like "food culture," "local specialties," and "activities." The core of quirk theory is that focusing on the unconscious—rather than just the outputs—allows us to grasp the region's true essence.

Morio: Concrete examples make this easier to understand, so let me give one here.

Centered around locally produced, high-value-added export items born from adversity—such as "Noda Salt," "Aramai Scallops," and "Mountain Grape Wine"—though produced in small quantities, the daily consumption of villagers supports the local production and consumption of agricultural and marine products.

Morio: Noda Village, introduced in the diagram above, is located on the northern coast of Iwate Prefecture. Its climate is cool and not particularly suited for agriculture. Furthermore, the sea is rough, with almost no sheltered bays, making even longline aquaculture difficult. Yet, from this history of coping with the adversities of nature and livelihood, they produce astonishingly high-quality products.

For example, "Noda Salt," highly sought after by major hotels; "Rough Sea Scallops," beloved even by Michelin-starred chefs; and "Wild Grape Wine," with its distinctive character that can compete even in standard wine categories. Like aikido, they absorb the power of adversity and use it to elevate their livelihoods.

Kagata: With that in mind, let's examine how each of our three speakers' regional backgrounds fostered unique characteristics and what cultures those characteristics have cultivated.

The "Everything Fast!" Food Culture of Bibai, Fostered by a Coal Mining Town

Morio: I was born in Hokkaido and raised in Tohoku, but when thinking of concrete examples of regional quirks, the first place that comes to mind alongside Noda Village in Iwate Prefecture is Bibai City in Hokkaido. A clear example is "Bibai Yakitori." The way you order yakitori at bars in Bibai is unusual. For example, if six people come in, they'll suddenly order a huge amount right when they sit down and order beer, like "36 skewers of offal!"

Kagata: Offal means chicken offal, right? I think the yakitori we know involves ordering more specifically, like "How many gizzards, thighs, skin, hearts, and livers each!"

Morio: Exactly. Basically, Bibai yakitori has an incredibly simple menu. It's just "Motsu" and maybe "Sho-niku" (regular meat). So customers always order 'X skewers of offal and X skewers of regular meat!' But the 'offal' in Bibai is unique—you get a single skewer loaded with various parts like chicken skin, gizzards, and other innards all together. Since people order huge amounts, it's served heaped high on a plate.

"Mibai Yakitori" boils down to just two menu items: offal and regular meat. The system is ridiculously simple: you walk in and state the number of skewers you want for your first order.

Kagata: I see. Thinking about the business benefits of this simple menu, first, orders and service are fast, right?

Morio: Exactly. Instead of ordering small portions of various things, you start with "Beer and a bunch of offal skewers!" Then everyone shares the huge pile that arrives. Since each skewer has slightly different offal parts, you never get bored.

Miyazaki: For the shop, in terms of ingredient management, it seems like situations like "We ran out of heart today" just can't happen. Plus, the moment customers arrive, you can probably start grilling the "offal" and "prime cuts" right away, right?

Kagata: They can predict, "We have X customers, so each will probably order 5-6 skewers," and start cooking accordingly. Now, looking at this food culture from the perspective of habits, is there an unconscious behavioral pattern like "We want it brought out quickly and in bulk"?

Morio: Yes. It's not just yakitori; there's a culture of wanting to eat quickly, eliminating any sluggishness. In Bibai, the time between ordering and receiving your food has to be fast. Another example is the famous "Bibai Yakisoba" – a bagged yakisoba noodle dish. It's pre-cooked yakisoba sold refrigerated in a bag. Of course, it's delicious when heated, but you can also just tear open the bag and eat it straight from there. In Bibai, middle and high school students buy it on the street and eat it while walking home from club activities (laughs).

Bibai's specialty, "Kadoya Yakisoba." Pre-cooked noodles are sold refrigerated in bags and can be eaten straight from the package. The legacy of the former coal mining culture lives on with today's junior high and high school students.

Kagata: Huh~, that looks delicious! You can definitely sense something like Bibai's unique character in this.

Morio: Bibai was originally a coal mining town. Essentially, miners would come up from the mines, unload the coal they'd extracted, and then immediately have to go back underground. They needed to eat a substantial amount in the short time they were above ground. I think both Bibai Yakitori and Bibai Yakisoba were developed so coal miners could eat something quick and easy.

Kagata: Right, Hokkaido has a coal mining culture, after all.

Morio: Another example: Kushiro ramen traditionally uses thin noodles. It's said this came about because miners working three shifts needed something they could eat quickly. In regions shaped by coal mining culture, people might unconsciously feel "Everything has to be done fast!" In Bibai, the coal mines are gone now (note: some companies still produce via open-pit mining), but I wonder if this quirk persists, albeit in a different form.

While coal production, once abundant, has drastically declined, there's now an effort to add value by utilizing another plentiful resource in Bibai: the "snow" of the heavy-snow region, the Sorachi Plain. For example, they store rice using the abundant snow accumulated during winter. This method not only avoids using electricity but also reportedly preserves the quality of the new rice better than rice cooled with electricity. Turning abundant local resources into added value— —might just be a modern-day variation of that "habit."

"We build even the bulky stuff ourselves" - Omitama City "Naturally welcoming outsiders" - Kamiyama Town

Kagata: I was involved in regional revitalization in Omita City, Ibaraki Prefecture, and found their culture fascinating—they'll build even quite substantial things themselves rather than relying on contractors.

Miyazaki: That DIY spirit, right?

Kagata: Exactly. For example, if there's an abandoned house, residents gather and convert it into a cafe. Omitama City is a small town with just under 50,000 people, yet theater is thriving there. Residents from various professions come together to put on a big annual performance. They make all the large and small props themselves. When we launched a local media outlet, many residents contributed articles.

Morio: So there's this habit of action: "Rather than relying on outsiders, let's just get our hands dirty and try it ourselves."

Kagata: Yes. The areas in Omitama City where dairy and livestock farming are currently practiced were apparently originally uncultivated land. It's a town that started with people pioneering and establishing dairy farming themselves, much like Portland, USA. And it was the grandparents of the current working generation—a not-so-distant generation—who built the town themselves. I think this has unconsciously ingrained a behavioral pattern where "doing things ourselves is just the norm."

Miyazaki: When tackling something, focusing on this "Omitama DIY spirit" could lead to interesting branding, both externally and for the local community.

Kagata: Exactly. It could offer a slightly different angle, just like we discussed in the previous article. Another regional quirk that comes to mind is Kamiyama Town in Tokushima Prefecture.

Morio: It's the town that gets mentioned when talking about regional revitalization, right? The one that made headlines with "Kamiyama Marugoto Technical College."

Kagata: Exactly. Many IT companies have gathered there, the number of newcomers is increasing, and it's considered a successful case of regional revitalization. Various analyses have been done on the reasons for Kamiyama Town's success, and I've also visited the area many times to hear people's stories. I asked around about the source of Kamiyama Town's uniqueness, and one story that made me think, "Ah, I see," was that "Kamiyama Town has a spirit that casually accepts even things that are different."

For example, there's that famous children's song, "The Blue-Eyed Doll," right? In the early Showa era, many dolls were gifted from America to various parts of Japan to promote friendship between the two countries. But then the war came, and many were lost. One of those dolls was discovered when Kamiyama Town's Kamiyama Elementary School relocated.

This led to the "Alice Homecoming" project, which aimed to return the doll to its American sender. This initiative sparked international exchange in Kamiyama Town, evolving into the "Kamiyama Artist-in-Residence" program in 1999, which welcomes and supports artists from overseas. Many artists have strong personalities, and with overseas artists, language barriers are often significant. Making this work in a remote mountainous area is truly remarkable. I found it very fitting that this history has led to the town welcoming IT companies as a new industry.

Morio: So Kamiyama Town already had a foundation for welcoming "outsiders," like international artists.

Kagata: Yes. But the story doesn't end there. Some suggest that underlying this is the "Ohenro" pilgrimage culture of Shikoku. In ancient Japan, towns deep in the mountains had the same faces forever, and human interaction was extremely limited. But Shikoku had the pilgrimage system, allowing people to interact and circulate even in the mountainous areas. Within that context, a culture developed where people would welcome and accept outsiders, even if they were somewhat different from the locals.

Miyazaki: I see! So, Shikoku as a whole had this pilgrimage tradition, creating fertile ground for kindness toward strangers from elsewhere. On top of that, Kamiyama Town saw increased interaction with foreigners after the discovery of the "blue-eyed dolls," and it naturally welcomes IT companies and newcomers even today.

Regional quirks are the "unconscious behavioral patterns" underlying "things and events."

Kagata: Now, we've looked at several examples, so let's organize this. Regional specialties and culture are the visible "things and events." In contrast, regional quirks are the "unconscious behavioral patterns" that underlie these things and events, born from historical circumstances. For example, in Bibai City, we identify the unconscious aspect of "Everything has to be done quickly!" as a regional quirk and focus our thinking on this.

Morio: And in this series, I hope we can delve deeper into the idea that by thinking in terms of quirks, we might uncover approaches to economic revitalization that are more deeply rooted in the region itself.

Miyazaki: How can we leverage these discovered quirks for regional revitalization? One thought is that since quirks are "unconscious" and "everyday," local people often don't see them as something to promote. For instance, grilled chicken skewers and yakisoba are completely routine for people in Bibai. But viewed from the outside, they hold potential from a tourism perspective.

Tourism generally seeks the "non-everyday," right? When we think "non-everyday," we often imagine "local specialties" or something luxurious. But immersing oneself in the quirks of a different culture is also profoundly non-everyday. In other words, it's possible that tourists coming to see the region's quirks, or companies focusing on them, could become a catalyst for locals to reexamine their own area.

Morio: That feeling of "the locals' everyday life" seeming like a parallel world to tourists is something I've noticed too, working in various regions. It's not the resort-like "extraordinary," but rather an everyday life different from our own – an "alternative everyday," if you will.

Miyazaki: Since quirks are things we naturally do anyway, incorporating them into regional revitalization initiatives that are conscious of the outside world can foster affection among locals. It also makes these initiatives easier to sustain. From that perspective, I think it connects to the previous discussion about how "locals actually want chain family restaurants or fast food outlets for regional revitalization" .

Is this the era where companies leverage regional quirks?

Morio: Abstracting that family restaurant and fast food discussion, I think it boils down to the theme of "national corporations and the future of regional areas." It's a bit of a stretch, but (laughs). For companies, declining populations and stagnant regions mean losing markets. Of course, with overall population decline inevitable, expanding overseas is crucial. But the domestic market is fundamentally a very strong base. So companies need to build win-win relationships with regional markets, not just sell products to them.

Miyazaki: Conversely, from the regional perspective, when considering the sustainability of the local economy, relying solely on municipal budgets and taxes may become unsustainable. So, the benefits of finding ways to effectively connect companies and regions are also strong for the local side.

Through this series, we aim to introduce the concept of "Kuse" and explore solutions together with companies and local communities. At this stage, we're beginning to see something emerge. Among the three of us, a hypothesis is forming: this "Kuse" – that is, a grounded sense of local identity – can connect with the "outside," generate profitable ventures and employment, build an economic sphere, and create a sustainable, positive cycle.

Kagata: I also feel that the marketing methods of large corporations, often called global or national companies, are facing a challenging phase. That is, the approach of "running uniform mass advertising nationwide to sell uniform products" – the sales tactic that suggests Tokyo's products are the coolest, or American products are the coolest. But people's lifestyles and values have diversified, making "one-size-fits-all products" less effective. Applying this to corporate expansion into regional areas, I think large companies should incorporate local "quirks" to be accepted by the community.

For example, a major apparel manufacturer now does live commerce where local store staff introduce products tailored to each region. After all, climates differ by area, so when people wear clothes and how they style them varies too. It makes no sense to use the same marketing for stores in Okinawa and Hokkaido, so they've shifted towards changing their broadcast content for each region.

Some companies might already implement measures like this, but by focusing even more on regional quirks, they could foster better connections and more easily gain local empathy and goodwill.

Morio: That's the idea of large corporations immersing themselves in the behavioral patterns of that region. Even when the same chain store expands, if they enter in a way that amplifies positive feelings toward the region or the happiness of living there, they should find it easier to gain goodwill from local people. Also, as we discussed last time, by making quirks visible as "shared tools," corporate regional strategies will likely change too.

Kagata: At the municipal level, discussions can get really personal and heartfelt. But there's still a gap in shared understanding between corporate players and local residents. To bridge that, starting conversations with locals by saying, "This quirk is interesting, isn't it?" can draw in people who were previously unengaged. Once those discussions happen, it's crucial to take the insights gained and translate them back into concrete systems.

Next time, the three of us want to try finding "local quirks" in practice!

<Summary of This Session>

- A region's "quirks" refer to the unconscious behavioral patterns of its people, shaped by its history, natural environment, and economic conditions.

- Discovering these quirks could unlock opportunities for industry and tourism.

- To build a win-win relationship between companies and regions, why not try incorporating these "quirks" into your marketing?