From left: Mr. Miyazaki, Mr. Kagata, Mr. Morio

This series features three unconventional planners from Dentsu Inc., who have been involved in numerous regional revitalization initiatives, proposing a new approach called "Regional Quirks."

*"Regional Quirks" refers to the "unconscious behavioral patterns" underlying a region. By revealing these "quirks" present in the background of all aspects—industry, tourism, local specialties—this initiative aims to foster sustainable economic zones across Japan. See Parts 1 and 2 for details!

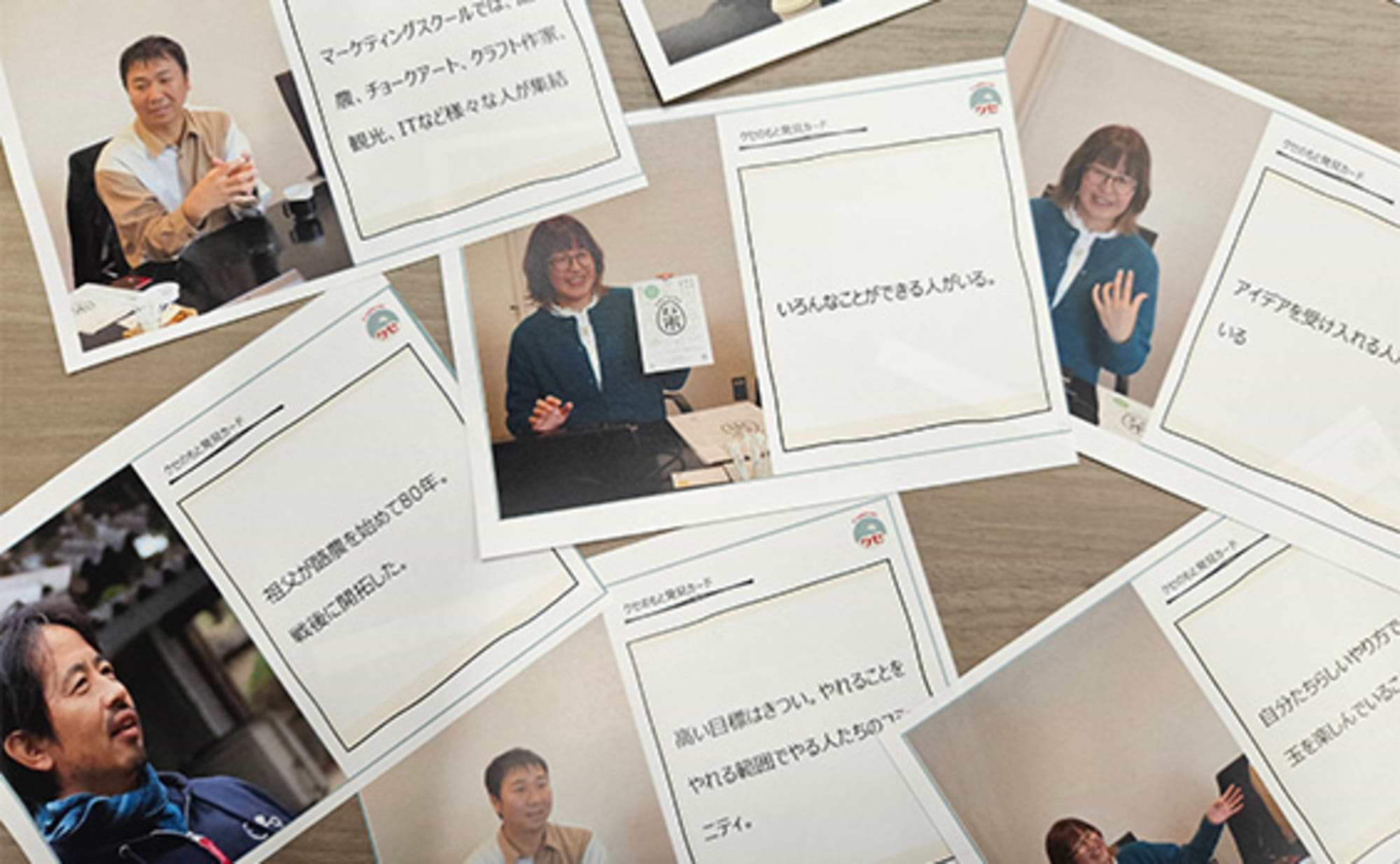

Last time, we introduced the Quirk Workshop, which uncovers regional quirks using "Quirk Source Cards" collected in Omitama City, Ibaraki Prefecture.

This time, we explore how to derive "regional growth potential (vision)" from the discovered regional quirks.

This session is brought to you by three "quirky experts": Toshiaki Morio from 47CLUB Inc., Takuya Kagata from the Global Business Center, and Nobu Miyazaki from Dentsu Inc. Business Transformation Creative Center.

The Sweet Trap of "Disconnected Visions" and "Vague Visions"

Kagata: Reflecting on this series' purpose again, it was about enhancing the sustainability of regional economic spheres, right? To achieve that, I've consistently thought that unique regional "quirks" could hold the key.

Morio: Yes. Our hypothesis is that extending these regional quirks to envision growth as "potential" leads to establishing a sustainable economic sphere. In other words, "drawing a growth vision for each region based on its unique quirks."

Kagata: However, creating a vision is easier said than done. The three of us have observed community development in various regions over the past decade. In that time, we've identified common challenges in vision creation that often lead to failure.

Morio: Failed vision creation can be broadly categorized into two types. The first is the "disconnected vision problem." This refers to setting distant goals that are disconnected from the region's actual reality. It's a trap often fallen into when companies from outside the region create regional revitalization visions. Local residents find it hard to internalize a vision that feels distant from their current lives, making it difficult to translate into action for growth.

Miyazaki: An example would be a vision like, "We'll invest massive budgets in land development, attract major corporations, and create jobs." This kind of vision isn't connected to their daily lives; it becomes a disconnected vision.

Kagata: So when it comes to "How do we actually achieve that vision?", people can't picture their next steps.

Morio: Another issue with corporate recruitment is that while it increases migration, it can create a society where the feelings of locals and newcomers don't intersect. Since the 1960s, Japan has built industrial parks across the country to attract large corporations and create jobs. While successful recruitment brings economic benefits, the perspective on whether that economy truly aligns with the region's identity was often missing.

Ideally, we want to create a society where newcomers also embrace the local quirks and work together to build new communities. This is part of the underlying reason we focus on regional characteristics. Another common pitfall in vision creation—Miyazaki-san, could you elaborate?

Miyazaki: The second challenge is the "vague vision." That is, creating a vision that's so abstract it could apply to any region nationwide. This has become particularly common over the last decade or so, since the government started allocating budgets for regional revitalization.

Kagata: Like visions such as "Creating a Happy Town Abundant with Greenery." They fit too many towns, making them somewhat generic, right?

Morio: That's precisely the problem with "fluffy visions." They don't become truly original plans for the community, which often leads to those driving the town development lacking motivation to engage fully.

What's fundamentally wrong with "disconnected visions" or "vague visions" is that they fail to make people feel personally invested. That's why we propose creating visions that are properly tied to the unique characteristics of each region.

Break free from "copy-paste policies." What is resource-expansion-type vision creation?

Mr. Morio

Kagata: Why do local governments end up with "disconnected visions" or "vague visions" in the first place? We three delved deep into this question as well.

First, in 2016, the "Regional Revitalization" movement began, spearheaded by Shigeru Ishiba, the first Minister for Regional Revitalization. The government then notified local governments: "If you don't formulate a comprehensive strategy, we won't allocate the budget." This prompted local cities across Japan to frantically start developing strategies.

For example, a regional city might face this:

"Your population will shrink to three-quarters of its current size over the next 30 years. How will you halt population decline and economic contraction?"

These highly challenging questions were posed, and various plans began from there.

And this is where the problem lies. Faced with "high difficulty and a timeframe of about 30 years," some local governments ended up creating "vague strategies." For instance, thinking some new industry might emerge, they'd say, "We'll attract IT companies."

Morio: Observing failed strategies and cases across regions, I've come to realize that plans won't succeed if they proceed without considering the area's economic growth and cultural preservation and development.

Miyazaki: It's common for outside companies to provide consultation, but the danger is that visions get created based solely on assets and numbers visible from the outside. This leads to every region adopting similar, essentially soulless visions.

Kagata: This is just one example, but there was a case where an external company had a "template" for creating visions, and they proposed applying the same template horizontally to every municipality. The problem was that there was no room for incorporating what the local people actually thought or the unique characteristics of that specific region.

Morio: I've also seen cases where comprehensive strategies ended up being identical across regions. While "horizontal deployment of successful models" is common in business, it doesn't apply to regional revitalization. I believe creating regional revitalization through "copy-paste" methods won't lead to happy outcomes.

Kagata: So, how do we avoid creating the "disconnected vision" or "vague vision" we've discussed? What's needed is to carefully observe the region's unique characteristics and reach a shared agreement on its "potential for growth" – what it can achieve. That's what I believe is referred to as "visioning" in technical terms.

Morio: "Growth potential based on regional characteristics" is, in other words, a "resource-expansion vision." Rather than forcing a "disconnect vision" or a "vague vision," we should capture the growth potential inherent in the region's characteristics and create a grounded vision that people can personally connect with. When aiming for high growth targets, or what's often called discontinuous growth, I feel it becomes even more crucial to start from the region's characteristics.

In this era, when planning based on "achievable growth targets," demanding discontinuous growth is generally important. However, if the discontinuity is too great, it becomes an imposed, detached goal for those carrying it out. That's precisely why discerning the region's unique traits and adopting a resource-expansion mindset— —might actually pave the way for discontinuous growth.

Portland and Noda Village are successful examples of capturing "local quirks"!

Mr. Kagata

Kagata: Looking overseas, Portland, Oregon—frequently ranked as "the most desirable city to live in" in various U.S. surveys—is a classic example of success achieved through decision-making that captures local quirks.

During the high-growth era of the 1970s, the entire United States was to be connected by highways, and the government was strongly pushing this plan. At the time, building highways to spread prosperity across the nation was considered both natural and wonderful. However, the result was that the construction of highways accelerated suburbanization in cities across the US, leading to the decline of downtown areas. Life became impossible without a car, causing hardship for those with lower incomes.

Amidst this, Portland formed a special citizen committee. The committee decided to "choose parks over highways," achieving the first highway removal in the United States. While the entire nation was charging ahead toward a car-centric society alongside highway construction, Portland chose a different path. Why was this?

Portland is located at the very edge of what was once the "frontier." During its settlement, the area was mostly forest. Its history involves the hard work of clearing the land and finally making it livable. Consequently, a "habit" of residents discussing and making decisions together became deeply ingrained. As a result, they concluded, "We can do anything ourselves, and we are perfectly content with our current way of life. We don't need a highway."

Miyazaki: Understanding their own habits well and firmly saying no to cookie-cutter solutions is what led to their current success.

Morio: Another success story I'd like to highlight is Noda Village in Iwate Prefecture, which was briefly mentioned in the second installment of this series. Recognizing the need for a comprehensive strategy unique to their community, they commissioned Dentsu Inc.

The resulting vision for the village was encapsulated in the phrase "A Village Where We Raise Each Other." Under this banner, they consciously nurture the local community and continue to raise children together with the residents. Specific initiatives include exchanges between farmers, fishermen, and children, with schools also cooperating.

For example, the school lunch center works within its limited budget to create and serve lunch menus themed around local specialties like "Aramai Scallops" and "Noda Salt." During these special meals, they invite the producers to give a one-hour lecture and then eat lunch together. By giving lectures to the children, producers also develop an awareness of "passing on their industry to the next generation." This creates a mutually nurturing relationship between children and producers. We believe this approach continues precisely because it embodies a "resource-expansion vision" that leverages and grows the community's existing resources.

Miyazaki: I've also visited Noda Village with Mr. Morio, and I was struck by how vibrant the local people were. I sensed many individuals confidently engaging in community activities, driven by a desire to leave something meaningful for the children.

Incidentally, a phrase like "A Village Where We Grow Together" doesn't need to be the residents' official "town slogan." It doesn't even need to be widely known among residents; it's enough if it permeates the minds of the behind-the-scenes players planning community development. Then, whatever they plan, they can think about it while keeping "growing and being nurtured" in mind. It's crucial that town hall staff, community development players, and industry leaders share this common awareness.

Morio: Perhaps it's better to share it among stakeholders for about three years, letting various facts accumulate before making it the town's slogan. If you just say the words without any context, it might feel awkward. But once the town's vision based on its unique characteristics ( ) has taken shape to some extent, I think it will be easier to accept.

What growth potential can we envision from the local quirks we discovered in Omitama?

Mr. Miyazaki

Kagata: Moving forward, I'd like us to explore what growth potential we can envision based on the regional quirks we discovered in Omita during the last workshop! First, here's the previous workshop's verbalization.

Laying out cards to reveal "local quirks"! Making the newly devised workshop a starting point for regional revitalization

https://dentsu-ho.com/articles/9208

Building on this, let's discuss. Komiyama will naturally face population decline going forward. But when it comes to things needed for daily life or work, even if it seems impossible, we "just make it while having fun." It feels like a waste to keep this trait confined only to Komiyama. I get the sense that about one in ten Japanese people want to live this kind of life. Komiyama has a population of just under 50,000, but there might be millions, even tens of millions, like this across Japan.

Therefore, by gradually sharing our local quirks with the outside world and creating many opportunities to "share" Komiyama's way of life, we could potentially increase the number of people visiting or moving to Komiyama. If new people gather from outside, chatting and making things should become even more enjoyable for local residents too. This is Komiyama's "potential for growth" – thinking from our local quirks – a path to expanding both our population and industry.

Morio: Since the town was originally formed by merging three municipalities, its openness to new members aligns perfectly with this growth potential and direction, doesn't it?

Kagata: Yes. When considering how to realize this, one environmental factor is the fact that "Omitama has Ibaraki Airport." Unfortunately, currently, many people arrive at the airport and fly out again without ever stepping into the town.

Komiyama City, Ibaraki Prefecture, was formed in 2006 by the merger of three municipalities. It's a relatively new local government, but according to Kakata, who has served as an advisor for several years, the residents have a strong sense of identity as "Komiyama citizens."

Another point: observing trends in society, we see that while there used to be a prevailing dislike for rural interpersonal relationships, now we've come full circle. More young people are thinking, "It's wonderful when neighbors from different professions gather to chat." There's also a growing trend of people finding it incredibly satisfying to make things themselves rather than buying everything. This isn't specific to Omitama; it's a broader societal trend.

By starting with these quirks, taking a fresh look at Omitama's resources, and considering broader societal trends, we can see opportunities for engaging "people who use Ibaraki Airport."

Through PR and outreach to target audiences, once they visit Omitama, creating opportunities for them to explore the town, chat with locals, or experience hands-on craft activities together – getting them to think "I want to come back to Omitama again" shouldn't be that difficult.

Miyazaki: Increasing the number of people involved, or the so-called "related population," is a challenge for any region. But by articulating the inherent local culture—those unique quirks—we can spark interest, making people think, "That sounds interesting. Maybe I'll try something in Komiyama."

In the "Quirk Discovery Workshop" covered in Articles 3 and 4, we collected quirk element cards like "Nature," "History," and "Livelihood." Conducting these workshops serves as an "inventory of the town." The factors that emerge there are also useful when considering the potential for growth in these quirks.

Kagata: Only when we work with local residents to figure out what kind of actions by what kind of people can healthily bring us closer to realizing that potential can we truly say the "Quirk Discovery Workshop" is complete. Furthermore, translating that into concrete "numbers" is also crucial. For example, even if we hold a market, how many people do we need to attract for it to be considered a "success"? If we don't set a target number, it just becomes a lively conversation at the bar that ends there.

Morio: Next time, to explore multiple case studies, we'll shift our focus to Kushiro, Hokkaido, and consider the growth potential of quirks!

<Summary of This Session>

1.Beware the pitfalls of regional vision-building: "Disconnected Visions" and "Vague Visions"

2.Create a "Resource Expansion Vision" that naturally extends from existing strengths

3.Use local strengths as a starting point to objectively assess regional resources and align them with broader societal trends!