This series delivers a digest of content from the book SNS History: The Future of a Society Connected by "Likes" (East Shinsho), published to commemorate its release.

Previous articles covered the following topics:

Part 1: Characteristics of the Three Major SNS Platforms and Why They Gained Support

Part 2: The Era of Searching for Information on SNS: The Shift from "Googling" to "Tagging"

Part 3: "Like!" as Innovation and the Principle of Imitation

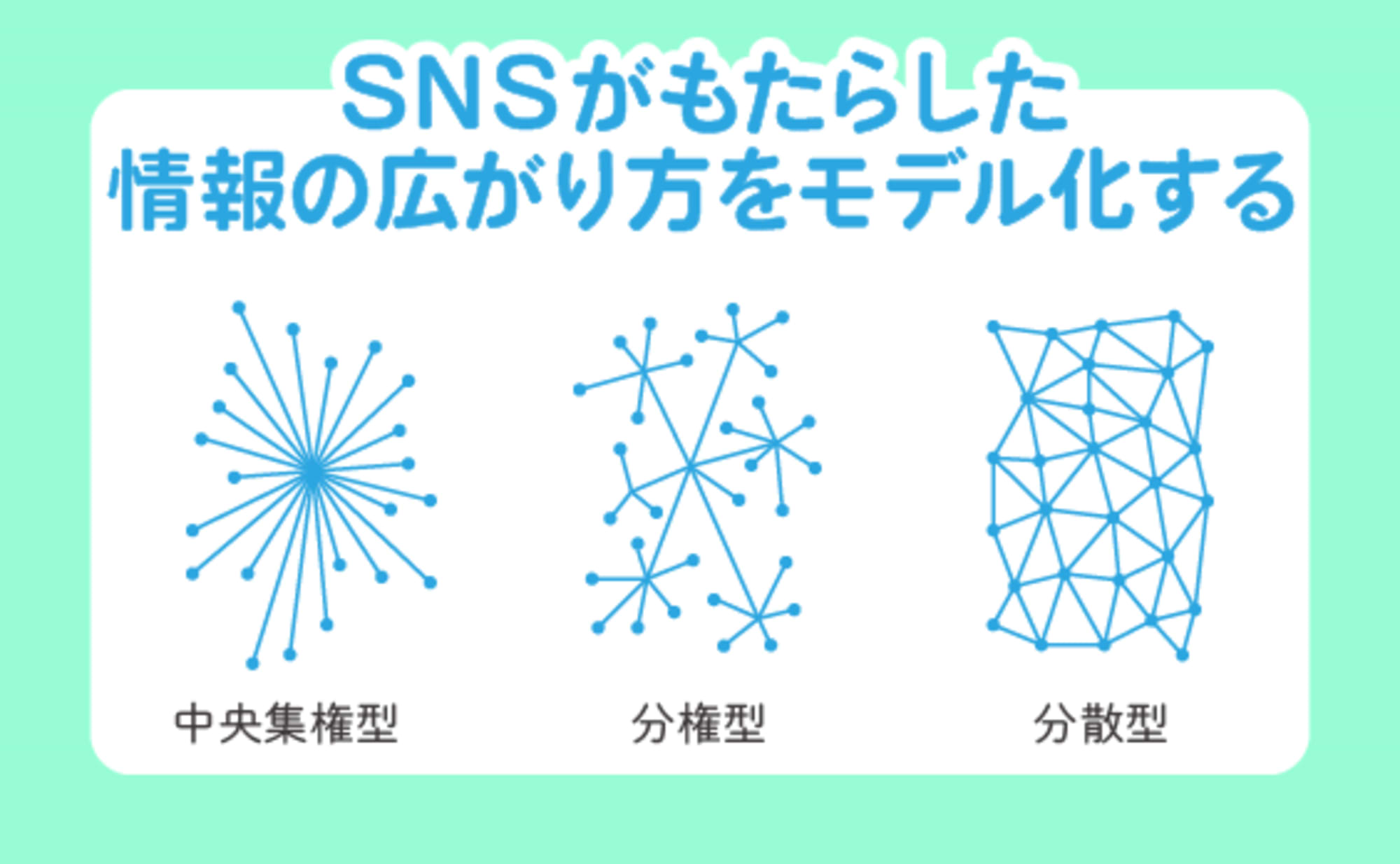

Part 4: Modeling How SNS Spreads Information

This time, we introduce the "buzz" phenomenon triggered by consumers becoming information creators, along with the "Three Ms" approach for companies to effectively engage with SNS.

"Buzz" Born in the SNS Era and Its Marketing Applications

As information spreads through SNS, leading to shifts in consumer attitudes and the emergence of trends, the concept of "Buzz" has gained attention. The original meaning of "Buzz" comes from the "Buzz-Buzz" sound made by flying bees, later evolving to mean noise or the lively chatter of people gathering to talk.

This term was adopted by the web marketing industry. It describes the grassroots spread of topics online, where people spontaneously discuss and amplify content. The phenomenon itself is called "going viral" or "buzz-worthy."

The term "viral" is also used with a similar meaning to "buzz." It describes how topics or ideas spread from person to person, much like an infectious disease spreading. While the analogy might seem poor, in the field of network science, the spread of rumors among people and the spread of viral infections are analyzed in the same way (considering how many countries saw the novel coronavirus spread explosively in a short period, one can truly grasp its transmissibility).

The word "buzz" carries the nuance of a "massive" volume of posts or shares occurring within a "short timeframe." While it can sometimes describe information spreading slowly, generally "buzz" is like a sudden, heavy downpour—unexpected, explosive, and fleeting. It happens unexpectedly, spreads rapidly, and the momentum doesn't last long or leave a lasting impact.

Defining the exact scope of what constitutes a "buzz" is also difficult. For example, former ZOZO president Yusaku Maezawa's "¥100 Million New Year's Gift Project" in early 2019 shattered the previous world record for retweets (3.55 million) and approached 5 million. This term can refer to such an extremely large-scale case, yet people also say something like a cute dog photo getting 10,000 retweets "went viral."

And neither interpretation feels out of place. The phenomenon of "going viral" is multifaceted, and it's important to note that the term itself carries this inherent ambiguity.

Interest in leveraging "buzz" for promotion and advertising communication is also high. This is because, among younger generations, awareness and favorability toward products and services often increase via social media. Companies dealing in consumer goods, especially food and beverages, particularly desire buzz phenomena with strong topic-generating power.

However, whether buzz translates into brand favorability is a separate issue. Even with meticulously planned and executed campaigns, the occurrence of "buzz" is not guaranteed.

We tend to think that if we have a good idea or an interesting initiative, it will be accepted by consumers and "go viral." However, according to the ideas presented in The Science of Serendipity (2012) by Duncan Watts, a prominent figure in the field of internet science, this might be a bit too optimistic.

Consider forest fires: whether one spreads or not depends on various variables and conditions at the time. No one thinks, "It was because the spark that started it was amazing!" However, Watts points out that when it comes to social phenomena caused by people, we tend to seek out reasons that satisfy us. In other words, it is a complex phenomenon that cannot be captured by a simplistic view like "if the content is good, it will go viral."

Concepts like "social contagion," introduced in the viral section, or "mimicry," as argued by René Girard in Part 3 of this series, are certainly important. But it's not as simple as "if the idea is good, or if a celebrity spreads it, it will go viral." It depends on the competitive news landscape at that moment, the situation and mood of the audience receiving the information, and the overall state of society. Like a forest fire, whether something "goes viral" or not is determined by the interplay of numerous variables.

Considering the Difference Between "Going Viral" and "Backfiring"

When addressing the theme of "buzz," one cannot avoid discussing its difference from "backlash."

Online bashing or concentrated critical attacks were called "comment scrums" until around the mid-2000s. This referred to comment sections on blogs or articles becoming chaotic. However, with the spread of SNS, attacks and condemnation regarding an issue began occurring simultaneously across various platforms, leading to the term "backlash" becoming established.

While both "buzz" and "backlash" represent the spread of topics on social media, they differ in that the former leaves a positive impression on the originator, while the latter leaves a negative one.

A crude pragmatism exists, suggesting that deliberately causing a backlash is a valid strategy to gain attention. Some even refer to this as "backlash marketing"—though it hardly qualifies as a strategy. Indeed, there are social media influencers who have gained notoriety by repeatedly provoking backlashes.

However, "flaming" has a harsh side where allies and enemies become starkly defined. It can leave wounds that the "it's profitable because it gets attention" mindset cannot fully heal—like people you thought were on your side turning against you. The danger remains that the visible scale of dissemination can create a false illusion of effectiveness.

The root cause of backlashes, simply put, is "self-centered communication lacking consideration for others' perspectives." This occurs when people spread misinformation based on ignorance or assumptions despite lacking true understanding, or when they feign objectivity to steer discussions for personal gain—examples include the "stealth marketing (stema) scandals" involving celebrities and influencers that have occurred several times since the 2000s.

We must sharply distinguish between "buzz" and "backlash" by focusing on the quality of information as it spreads.

The Three Ms of SNS Management: "Monitoring," "Mingling," and "Measuring"

While the frenzy surrounding "buzz" seems to have cooled somewhat, the magic of information spreading organically continues to captivate us. A world without buzz would undoubtedly be dull.

However, we need not only magic but also a methodology grounded in logic.

To maintain that level of calm, let's introduce the "Three Ms" – a standard approach primarily for companies and organizations utilizing SNS.

The three M's refer to the following:

"Monitoring" (observing)

"Mingle" (to interact)

"Measuring" (Measuring)

"Monitoring" essentially means social listening. It involves carefully observing and understanding what kind of communication users are engaging in and what topics are being discussed. It's profoundly important to grasp not only the voices and needs of your own company or brand's fans but also those of the general public.

Illustration: Haruka Watanabe (Dentsu Inc.)

"Mingle" means deepening relationships through interaction with other accounts/users. This broadly encompasses not only replying to comments with comments, but also liking posts, retweeting to spread content, and aggregating interactions in some form.

"Measuring" means implementing the PDCA cycle to move closer to optimal management. While unnecessary for personal hobby-based social media, it's an essential process when pursuing business objectives. It involves adjusting post content and management strategies based on measurable engagement metrics on social media.

The key to integrating these three is understanding how the value from "Monitoring" and "Mingle" translates into "Measuring." We must reevaluate whether we're setting short-sighted goals and measuring without this perspective.

Social media management mindful of these "Three Ms" will help build lasting engagement with consumers. And by deepening our understanding of consumers through such management, we can expect to encounter "buzz" somewhere along the way.