【Table of Contents】

▼Solution Journalism: How Problem-Solving Reporting Revitalizes Communities

▼Case Study: Shimotsuke Shimbun - Revitalizing Downtown Areas and Gaining Fans by Opening a "News Cafe" as an Information Hub

▼Fukui Shimbun Case Study: The "Stork Branch Office," where reporters actually lived in the satoyama, mobilized the prefecture

▼Kobe Shimbun Case Study: Implementing Diverse Initiatives Through the "Regional Partner Declaration" to Revitalize Hyogo Prefecture

▼All Regional MediaMust EmbraceValue Transformation to Gain Residents' "Empathy"

Solution Journalism: How Problem-Solving Reporting Revitalizes Communities

This article explores "How regional media will survive going forward." As a prelude, I'd like to discuss the 65th All Japan Advertising Federation Kobe Convention held in May. ( See the report article here )

The All Japan Advertising Federation, whose members are advertising associations from various regions, holds a national convention annually, rotating among its member associations. At the 2017 Kobe Convention, a commemorative relay presentation was held under the keywords "150th Anniversary of Port Opening," "Disaster and Bonds," and "The Future of Advertising," with the author serving as moderator. What emerged from this event offered hints for the survival of local media.

The All-Japan Advertising Federation Kobe Convention held in May

One example is the Kobe Shimbun. Twenty-two years after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, as fewer people directly experienced the disaster, there is a growing need to pass down the stories to prevent memories from fading and to raise individual awareness of disaster preparedness.

To address this, the Kobe Shimbun partnered with university students from generations unfamiliar with the disaster to launch the "117 KOBE Disaster Prevention Committee." By conducting disaster prevention and lifesaving training across university boundaries, they cultivate "117 KOBE Disaster Prevention Masters" equipped with disaster knowledge. They spread awareness of these activities via social media and other channels to recruit more participants.

Another example is the initiative by Sendai Broadcasting and Iwate Menkoi Television, presented by Hakuhodo's Airo Takabashi.Following the Great East Japan Earthquake, these two disaster-affected TV stations, together with Mr. Takabashi, launched the "Sanriku Work Project, " which created "Hamano Misanga 'Kai'." The goal was to give hope for tomorrow to women who lost their jobs by having them weave friendship bracelets from fishing nets rendered unusable by the disaster, generating income.

First, as a "strong entry point," they focused on delivering a powerful message through simple, well-organized content and compelling visuals. Then, as a "broad exit point," they aimed for wider dissemination by leveraging social media sharing and spreading, while also targeting mass media coverage starting from Sendai Broadcasting and Iwate Menkoi Television. As a result, they sold a cumulative total of 170,000 sets, achieving sales exceeding 100 million yen.

Both projects encompass the theme: "What can local media do to revitalize their communities?"

Local media, deeply rooted in their communities, face life-or-death stakes with the region's decline or growth. For media to operate stably and sustainably, the region must thrive, which requires solving local challenges. No matter how much the media reports on regional issues, it means nothing to residents unless those issues are actually "solved."

When media goes beyond mere reporting to actively engage in solving societal and regional problems, it is called " solution journalism " (*).

*This concept gained traction after Harvard University's Nieman Journalism Lab, renowned for media and journalism research, introduced it in 2013 as "A new, mainstream - solutions journalism."

What's crucial in solutions journalism is that media don't unilaterally provide solutions; they tackle challenges together with the people (local residents). Engaging residents allows for shared understanding of problems and the creation of effective solutions. Above all, it fosters "empathy" between media companies and residents. It enables media companies to be recognized as "essential entities for the community."

Surveys like J-READ indicate that while local media enjoy high "trustworthiness" among residents, their scores for "approachability" and similar metrics are not particularly high. By solving problems while simultaneously building community with local residents, and turning residents into fans and supporters of the media, a sustainable symbiotic relationship is created.

Solution journalism describes this relationship with residents as "engagement," a well-known concept in marketing that means "building positive relationships between companies and residents."

Several practical examples already exist in Japan of revitalizing communities through solution journalism. Below are three examples from fiscal years 2013 to 2015, in which the author was deeply involved and which won the Newspaper Association Award in the Management Operations category.

Shimotsuke Shimbun Case Study:

Revitalizing the downtown area and gaining fans by opening a "News Cafe" as an information hub

The hollowing out of central business districts is a major challenge for regional cities. In Utsunomiya City, the central business district lost customers to roadside stores, leading to a situation characterized by "large store closures," "vacant small shops," and "the emergence of shuttered streets."

This also dealt a blow to the local Shimotsuke Shimbun. News from the downtown area dwindled, circulation within Utsunomiya began to decline, and advertising revenue simultaneously decreased.

The company embraced revitalizing the region as its own mission, declaring its goal to become "a newspaper company cherished by the community" and committing to finding solutions. One initiative was the "Shimotsuke Shimbun NEWS CAFE," opened in June 2012 facing the main thoroughfare, Orion-dori. It was Japan's first "permanent café themed around news and operated by a newspaper company."

The first floor is a café where patrons can relax with coffee or locally produced juices while reading that day's Shimotsuke Shimbun. The second floor is freely open for hosting small events, becoming a hub for community interaction where local businesses and organizations hold exhibitions, meetings, music events, rakugo performances, and more almost daily. The third floor houses the Shimotsuke Shimbun Utsunomiya Downtown Branch Office, also functioning as a base for disseminating information from the central city area.

By offering free event space, Shimotsuke Shimbun NEWS CAFE also serves as a gathering place for local residents.

For past articles, see

here.

This cafe operates on two core principles: first, to disseminate vibrant information within the "town center" and contribute to regional revitalization; second, to maximize the potential of the Shimotsuke Shimbun itself, thereby increasing its fan base.

Noteworthy is the focus on "increasing fans" rather than "increasing subscribers." The concept of building a stable foundation in the community by "increasing fans," even if it doesn't directly lead to purchases, is likely to become indispensable for local media going forward.

After the cafe opened, people gradually returned to Orion Street. New shops opened, and the area began regaining its former liveliness. Regular surveys showed results indicating revitalization of the local shopping district, and scores for residents' familiarity with the paper also improved across the board. Shimotsuke The newspaper has become a more familiar presence in people's lives.

Fukui Shimbun Case Study:

The "Stork Branch Office," where reporters actually live in the satoyama, moved the prefecture

Fukui Prefecture, also known as the birthplace of the premium rice brand "Koshihikari," is a land of abundance. Its residents enjoy high satisfaction, benefiting from agricultural products nurtured in the satoyama (traditional woodland) and seafood from the Sea of Japan. However, recent depopulation has led to the deterioration of the satoyama, and the stork, once a symbol of its richness, had disappeared.

The initiative to bring the cranes back to Fukui Prefecture began with the "Fukui Shimbun Stork Branch Office." A reporter moved into a 100-year-old traditional house in the Hakusan district of Echizen City, an area with deep ties to the cranes, and lived there as the "branch office." While experiencing satoyama life firsthand, the reporter sought ways to protect and utilize the environment to make it suitable for the cranes to inhabit.

By becoming active participants in satoyama management—such as growing pesticide-free rice alongside local farmers—the journalists could write about the challenges and charms of satoyama from the same perspective as their readers. When writing articles, they consciously expressed their own feelings, shifting from "objective reporting" to "participatory reporting." Seeing this, local residents also began actively cooperating with initiatives like pesticide-free rice farming, leading to the return of ecologically rich satoyama.

The following year, storks returned early. But the project didn't stop there; Fukui and Hyogo Prefectures collaborated on a stork reintroduction program. This case demonstrates how a newspaper's commitment to solution journalism can mobilize government and revitalize a region.

The Stork Bureau, established in a repurposed vacant traditional house. This initiative drew in many people, creating a powerful ripple effect.

Following the satoyama revival, the Fukui Shimbun turned its attention to revitalizing the city center. The area around Fukui Station in Fukui City had lost its former vibrancy due to population decline. Meanwhile, plans were confirmed for extending the Hokuriku Shinkansen to Fukui, making the development of the station area a key challenge ahead of the bullet train's arrival.

While discussions among experts, led by the administration, dragged on for years, an executive of the Fukui Shimbun declared, "We've exhausted the debate." From then on, the newspaper's mission became solving the problems revealed in those discussions, such as depopulation. This led to the project " How to Start Town Development: Reporters on the Move." Drawing on the experience of the Stork Branch Office, reporters themselves established a town development base in front of the station and began various activities centered around it.

Kobe Shimbun Case Study:

Through its "Regional Partner Declaration," it implemented various initiatives to revitalize Hyogo Prefecture

The Kobe Shimbun, which we mentioned at the beginning with the "117KOBE Disaster Prevention Committee," launched the "Regional Partner Declaration" under the slogan "Let's Work Together More" to revitalize the region. This is a large-scale initiative to transform the company into an entity recognized as a partner for the citizens of Hyogo Prefecture.

The "117KOBE Disaster Prevention Master Project," a collaborative effort between university students and the Kobe Shimbun, gradually gained traction through social media.

Existing initiatives include the " Kobe Shimbun Child-Rearing Club Skip " supporting parenting, the " Life Support Project " conducting security patrols and community watch activities in collaboration with retailers, and a regional partnership agreement with Asago City, home to the famously "castle in the sky," Takeda Castle.

Additionally, the Kobe Shimbun is involved in the disaster recovery support project " Everyone's Sunflower Heart! Project." This initiative involves distributing sunflower seeds—a symbol of brightness and vitality—to encourage people nationwide to grow sunflowers. The seeds are then used to produce sunflower oil, with the proceeds supporting disaster-affected areas. The number of participants growing sunflowers has spread across the country, garnering widespread support.At the Zen-Kōren Kobe Convention, a ceremony was held to present donations from the " " to the areas affected by the Kumamoto Earthquake.

All regional media must confront a value shift to earn the "empathy" of local residents

The three cases introduced here each won Newspaper Association Awards, and all can be said to have been recognized for their "transition to solution journalism."

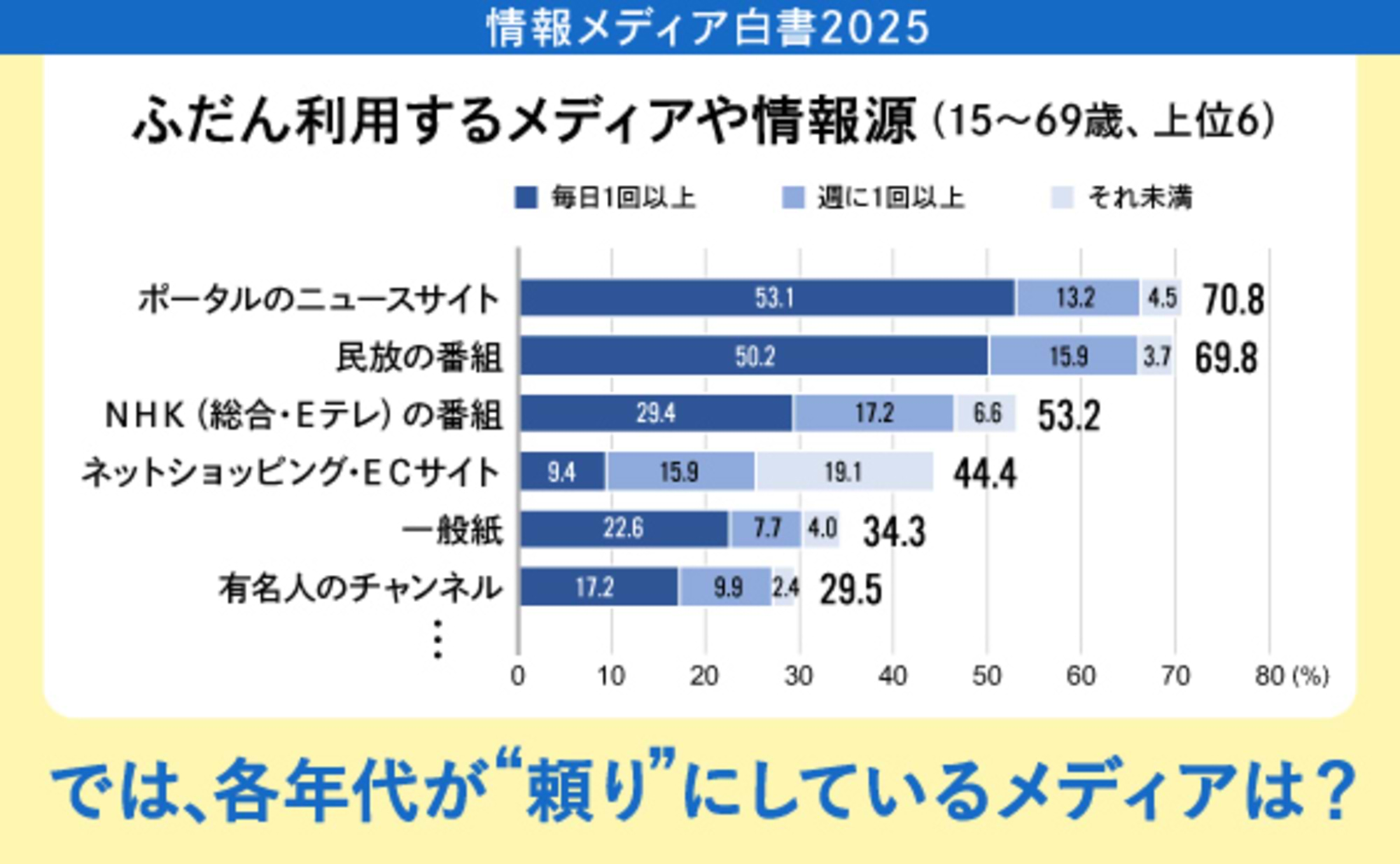

Numerous surveys show that "local media enjoy high trust levels among local residents." However, as Kotler's Marketing 4.0 also states, corporate value has now changed, and we have entered an era where businesses that fail to resonate with consumers are not chosen.

Moving forward, emotional value—such as "empathy" and "becoming a fan"—will become increasingly crucial, going beyond the functional value of "trust." To survive, media companies must confront the need to shift away from the uniform value of "reporting."